I have written this account in the solitary hours after midnight, when the house lies silent and my hands cease their trembling long enough to hold the pen. I write it knowing I shall never speak of what I witnessed, yet unable to bear the weight of it alone. Perhaps some distant relation, sorting through my effects long after I am dust, will discover this letter and dismiss it as the ravings of a mind unhinged by what it saw. Let them think so. It is a kinder conclusion than the truth.

My name is Dr Edward Chenowith, and I practise medicine in the city of London. On the evening of 14th November, 1888, I was summoned to attend a patient in Clerkenwell, a watchmaker by the name of Josiah Thorne. The message had reached me late in the afternoon, and I had sent word that I would call upon him after completing my rounds at the hospital. It was past nine o’clock when my carriage finally stopped before a narrow building wedged between a tailor’s shop and a tobacconist, its front windows dark save for a faint glow emanating from the upper storey.

The woman who admitted me—a Mrs Hadley, the housekeeper—was grey-faced with worry. “He’s been asking for you these past three hours, Doctor,” she said, wringing her hands. “The fever’s got worse, and he’s saying such strange things. I fear his mind is going.”

I assured her that delirium was common in cases of severe influenza, and followed her up the narrow staircase to the bedchamber. The room was overwarm, a fire blazing in the grate despite the mildness of the evening. The air was thick with the smell of camphor and something else—a peculiar metallic scent I could not immediately place.

Josiah Thorne lay propped against several pillows, his face flushed with fever, his nightshirt soaked through with perspiration. He was a man of perhaps seventy years, though illness had aged him further. His hands, resting atop the counterpane, were those of a craftsman: long-fingered, steady despite the tremor of fever, marked with the tiny scars and calluses of decades spent working with delicate mechanisms.

“Dr Chenowith,” he said, his voice hoarse but urgent. “At last. You must forgive me—I know you have come from far, and I am grateful.”

“Not at all, Mr Thorne,” I replied, setting down my bag and approaching the bedside. “I apologise for my tardiness. I have come directly from Belgrave Square, where I was attending the death of Lord Ashworth. The poor man finally succumbed this afternoon.”

I saw Thorne’s expression change—a flicker of something I could not quite identify. Pain, perhaps, or recognition. His fingers clutched at the bedclothes.

“Ashworth,” he repeated, the name barely a whisper. “Then it is finished. The last of them.”

“Did you know the family?” I asked, reaching for his wrist to check his pulse.

“Know them?” A strange, bitter smile crossed his face. “In a manner of speaking. His daughter—Lady Eliza—she disappeared forty years ago. November of 1848. Vanished from her bedchamber in the night without a trace. He never recovered from the grief of it.”

I nodded, remembering the story vaguely from my childhood. It had been a scandal at the time—a young woman of good family, engaged to be married, simply gone. There had been theories, of course: elopement, abduction, murder. But no evidence, no body, no resolution.

“A terrible tragedy,” I said. “But Mr Thorne, you must not agitate yourself. Your pulse is racing, and your fever—”

“The fever is the least of what ails me, Doctor.” His hand shot out with surprising strength and grasped my wrist. His eyes, bright with fever and something more desperate, fixed upon mine. “I am dying. I know it, and you know it. But before I go, I must confess. I must tell someone, or I shall carry it with me into whatever judgement awaits.”

I had heard many deathbed confessions in my years of practice—admissions of infidelity, confessions of crimes long past, reconciliations sought too late. I assumed this would be another such unburdening, the fevered guilt of a dying man seeking absolution. I nodded, settling into the chair beside his bed.

“If it will ease your mind, Mr Thorne, then speak. I am bound by my profession to keep your confidence.”

He closed his eyes for a moment, gathering strength. When he opened them again, they were distant, looking not at me but at some point far beyond the walls of that close bedchamber.

“I was a young man then,” he began, “perhaps thirty years of age. I had already made a name for myself as a craftsman—my timepieces were sought after by the wealthy, prized for their accuracy and beauty. I took commissions from lords and ladies, from merchants who had made their fortunes and wished to display their wealth. Each piece was unique, a work of art as well as precision engineering.

“But I had a secret, Doctor. For every commission I accepted, I created not one timepiece but two. Twins, identical in every respect save for one crucial detail: the piece I delivered to my patron was perfect, flawless. The piece I kept bore a hidden mechanism, a locking lever concealed within the case. When activated, it would stop the twin piece—stop it absolutely, freezing it at whatever hour, minute, and second I chose.”

He paused, his breathing laboured. I offered him water, which he sipped before continuing.

“You think me mad already, I see it in your face. But it is true, Doctor. I discovered this property quite by accident whilst working on a commission for a duke. I had created a matched pair—not intentionally, merely as a test of my skill, to see if I could replicate a design exactly. When I was adjusting the mechanism of one, the other stopped. Completely stopped, though it was in another room, wound and running perfectly moments before.

“I tested it again and again, unable to believe what I was seeing. But there was no denying it: some sympathetic connection existed between the pieces, some property of their perfect similarity that I could not explain but could certainly exploit.”

“Mr Thorne,” I interrupted gently, “the fever—”

“Is not making me rave!” His voice rose, and he fell into a fit of coughing. When he recovered, he fixed me with a desperate stare. “Please, Doctor. Let me finish. You will understand soon enough.

“I began to use this discovery. When I delivered a timepiece to a patron, I would wait until nightfall, then activate the locking mechanism on the twin I had kept. The effect was immediate and absolute: the owner of the other piece would be suspended, trapped in a single moment. Time continued around them, but they themselves were held fast—unable to move, unable to speak, conscious but utterly helpless.

“And whilst they were thus imprisoned, I would enter their homes and take what I pleased. Jewels, coin, papers that might be sold to interested parties. I was never greedy—I took only what would not be immediately missed, what might be attributed to carelessness or the dishonesty of servants. And after an hour, perhaps two, I would release the mechanism. They would continue from the precise moment where they had been stopped, unaware that any time had passed, that they had stood immobile whilst a thief walked freely through their halls.”

I sat back in my chair, studying his face. The tale was fantastical, impossible, yet he spoke with such conviction, such precise detail. I had heard delirium take many forms, but this was remarkably coherent for a fevered dream.

“For five years,” he continued, “I profited from this arrangement. I grew wealthy—wealthy enough to expand my workshop, to take on apprentices, to be invited into the very society I was robbing. I told myself I was not truly harming anyone. They did not know what had happened to them. They lost a few trinkets, nothing more. The guilt was manageable, buried beneath the thrill of my secret power.

“And then I met Eliza Ashworth.”

His voice softened on her name, and the bitter expression melted into something else—longing, regret, grief compounded and compressed until it had become something solid and permanent, a stone lodged in his chest.

“She was nineteen years old, beautiful in a way that seemed to belong to another age. Dark hair, pale skin, eyes the colour of slate. But it was not her beauty that captivated me—it was her mind. She visited my workshop with her father, who wished to commission a piece for her upcoming marriage. She asked questions about my work, about the mechanisms, the mathematics of gears and springs. She understood, Doctor. She saw the artistry in what I did.

“I fell in love with her that very day. Madly, completely, with the obsessive precision I brought to my craft. I convinced myself that she felt the same, that the interest she showed was not mere politeness but genuine affection. I began calling at the house in Belgrave Square, ostensibly to discuss the commission. Her father approved—I was respectable, successful, no longer the poor clockmaker’s son I had been born. He permitted me to speak with her, to walk with her in the garden whilst he attended to business.

“I built for her the most beautiful clock I had ever created. A mantel clock of rosewood and brass, with a face of white enamel painted with forget-me-nots. The mechanism was flawless, the chime sweet as church bells. When I presented it to her, she wept at its beauty. And I, emboldened by what I mistook for her feelings, proposed marriage.

“She was gentle in her refusal. She explained that she was already engaged, that she held great affection for her intended, that she hoped we might remain friends. She insisted I keep the clock—she could not accept such a gift when she could not return my feelings. It would not be proper.

“I returned to my workshop that night in a state I can barely describe. Humiliation, rage, grief—they twisted together inside me until I could not tell one from another. I looked at the clock she had rejected, so beautiful, so perfect, and I hated it. Hated her for not wanting it, for not wanting me.

“And then the thought came: if she would not accept my gift willingly, I would give her one she could not refuse.”

He closed his eyes, and I saw tears slip from beneath the lids, tracking down his fever-flushed cheeks.

“I worked for three weeks, barely sleeping, barely eating. I created a perfect twin of the clock—identical in every detail, down to the placement of each painted flower on the dial. But in this second clock, I installed the mechanism. The locking lever, hidden behind a panel that only I knew existed.

“I returned to Belgrave Square and begged an audience with Lady Eliza. I told her I had reconsidered, that I understood her position, that I wished only for her happiness. And I asked if she would reconsider accepting the clock, as a token of our friendship, a reminder of the time we had spent together. She was relieved, I think, that I had accepted her answer with grace. She took the clock and had it placed on the mantel in her bedchamber.

“A week later, I called again. I asked her to reconsider my proposal. I had convinced myself, you see, that she simply needed time, that her engagement was one of convenience rather than love, that she would come to see we were meant for each other.

“She told me she had married three days prior. A quiet ceremony, just family. She was Eliza Barrett now. She was kind about it, but firm. There would be no reconsideration. She wished me well and asked me not to call again.

“I walked home in a daze. All my planning, all my hoping—it meant nothing. She was lost to me, and I had only myself to blame for waiting, for assuming, for not understanding that her kindness was not love.

“But I had the twin clock, Doctor. I had the mechanism. And at midnight, mad with grief and rage, I stopped it.”

His breathing had become more laboured, and his hand clutched at his chest. I moved to examine him, but he waved me away.

“Let me finish,” he gasped. “Please. I am not long for this world, and you must know it all.

“I returned to Belgrave Square at one o’clock in the morning. The servants had retired. I knew the house—Lord Ashworth had commissioned pieces from me before, and I had been a guest there. I let myself in through the garden door.

“The house was utterly still. Silent in a way that went beyond mere quiet—it was the silence of stopped time. In the drawing room, I found a maid caught in the act of banking the fire, the poker raised, a log suspended above the grate. In the hallway, a footman stood motionless, a candle in his hand, his mouth open as if he had been speaking when midnight struck.

“I climbed the stairs to her bedchamber. My heart was pounding so violently I thought it might burst. I told myself I only wanted to see her, to look upon her one last time. But I knew, even then, what I intended to do.

“She was standing before her mirror, preparing for bed. Her hair was down, and she wore a white nightgown. Her hands were raised to her neck, unfastening a necklace. She looked like a statue, like Galatea before Pygmalion’s kiss. Beautiful. Untouchable. Mine.

“I released the mechanism at two o’clock. I had been standing there for an hour, simply looking at her, and I could not bear to stop her time again, to trap her once more. But when I released it, she did not move. She remained exactly as she had been, held in that moment.

“It took me some time to understand what had happened. An hour outside of time—that was what I had given everyone in that house. To them, no time had passed at all. The maid would complete her gesture, the footman would finish his sentence. They had lost nothing, gained nothing. It was as though that hour had simply never been.

“But Eliza—I had stopped her at midnight and released her at two o’clock. She had lost two hours. And in those two hours, her body had remained precisely as it was at midnight, whilst the world moved on around her. When I released the mechanism, time did not catch up. She remained stopped, held fast in that instant, whilst everything else continued.

“I had created a paradox, Doctor. A rupture in time itself. And Eliza was caught in it, suspended in the moment when her clock stopped, unable to move forward.”

“Dear God,” I whispered, though I still believed this to be nothing more than a fever dream.

“I panicked. I lifted her—she weighed nothing, suspended as she was—and I carried her from the house. No one saw me. How could they? They were all still trapped in their own stopped moments. I brought her here, to my workshop, and I laid her in the room below. And there she has remained, Doctor. For forty years, she has remained exactly as she was on that November night in 1848.”

The room seemed suddenly colder, despite the blazing fire. I stared at Thorne, searching his face for signs of delusion, of madness. But I saw only terrible, lucid despair.

“At first,” he continued, his voice dropping to barely a whisper, “I told myself she would wake. That the effect would fade, that she would forgive me. I kept her in comfort—I arranged the room below as a chamber fit for a lady, with fine furniture and soft light. I spoke to her, read to her, told her of my day. I convinced myself we were together, that this was what I had wanted.

“But as the years passed, I began to understand what I had done. Not just to her, but to her family, to all those who loved her. I heard of the search, the scandal, Lord Ashworth’s grief. I watched him grow old before his time, watched the light leave his eyes. And I knew I was responsible, knew that I had destroyed not just Eliza’s life but his as well.

“I wanted to release her, Doctor. God knows I wanted to. But I was afraid. Afraid of what would happen when forty years caught up with her in an instant. Would she age? Would she die? Would she crumble to dust, or would she simply continue from that moment, young and confused, in a world that had moved on without her? I could not bear the thought of causing her more harm. And so I did nothing. I kept her there, suspended in time, whilst I grew old with the weight of what I had done.

“But now I am dying. I am leaving this world, and I cannot leave her trapped here, cannot let her remain after I am gone. Mrs Hadley does not know about the room below—I have kept it locked, told her it is storage for old mechanisms and tools. When I am dead, no one will know Eliza is there. She will be abandoned, forgotten, trapped for eternity.

“So I tell you this, Doctor, because I have no choice. The fever has made me brave, or mad, or both. When I am gone, you must go downstairs. You will find the door to the workshop behind the staircase. Take the key from my waistcoat—it is the brass one, smaller than the others. Inside, you will find the room where she waits. And on a shelf, you will find a clock with forget-me-nots painted on its face. Turn the lever inside the back panel. Release her. Let her go to whatever fate awaits, but do not let her remain trapped here.”

His hand found mine again, clutching with desperate strength.

“Will you do this, Doctor? Will you grant an old man’s dying wish?”

I looked into his eyes—fevered, pleading, terrified—and I did what any physician would do when faced with a patient in such distress. I nodded.

“I will,” I said, though I believed I was humouring a dying man’s delusions. “I give you my word.”

The relief that flooded his face was profound. He sank back against the pillows, his grip loosening.

“Thank you,” he whispered. “Thank you. Perhaps now I can rest.”

I stayed with him for another hour as his breathing grew more laboured, his fever climbing higher. At half past eleven, he fell into unconsciousness, and at midnight—that hour which had held such significance in his tale—his breathing stopped entirely.

I checked for a pulse, found none, and sat back with a sigh. Josiah Thorne was dead.

Mrs Hadley wept when I told her. I helped her make the arrangements, sent word to the undertaker, performed all the duties expected of a physician in such circumstances. And all the while, his words echoed in my mind. The room below. The clock. Eliza Ashworth, suspended for forty years.

It was nonsense, of course. The ravings of a fevered mind. But I had given my word, and more than that, I found I could not leave without satisfying my curiosity. What if there was a room below? What if some poor woman was trapped there—not suspended in time, that was impossible, but perhaps held captive all these years, mad or comatose?

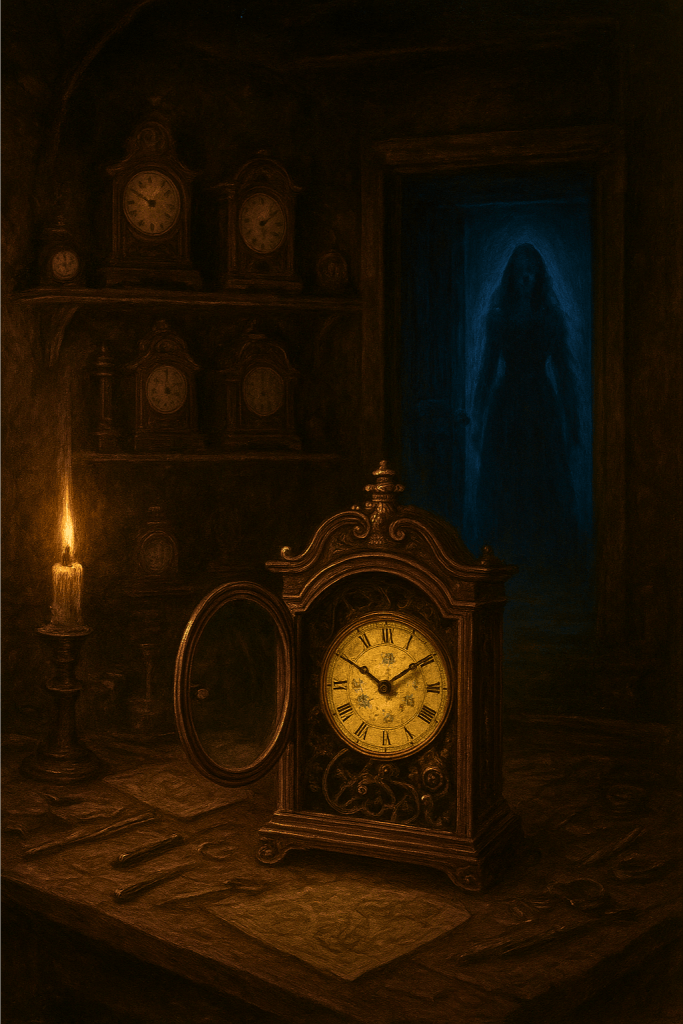

At two o’clock in the morning, after Mrs Hadley had retired to her own room to grieve, I found myself descending the narrow staircase. The workshop was on the ground floor, behind the shop front where Thorne had met with customers. I found the door he had described, partially hidden behind the staircase, and tried the handle. It was locked.

I reached into the pocket of Thorne’s waistcoat, which I had kept with me, and found the brass key. My hand trembled as I fitted it into the lock. The mechanism turned with a soft click, and the door swung open.

What I found beyond defies all reason, all natural law, all scientific understanding. Yet I swear upon my honour as a physician and a gentleman that what I write here is the truth.

The room was perhaps fifteen feet square, fitted out as Thorne had described: fine furniture, soft light from a gas lamp turned low, walls hung with blue silk. And in the centre of the room, standing before a mirror in a white nightgown, her hands raised to her neck, was a young woman.

She did not move. She did not breathe. She was utterly still, more still than any living thing should be. Her skin was pale, perfect, showing no signs of decay or age. Her eyes were open, fixed on her own reflection, the grey irises clear and bright.

I approached her slowly, afraid that any sudden movement might shatter whatever spell held her. I reached out a trembling hand and touched her arm.

It was neither warm nor cold—it simply was, as though temperature had no meaning. The flesh yielded slightly beneath my fingers, yet she remained absolutely motionless. It was like touching a wax figure, yet I knew with absolute certainty that this was no sculpture. This was—had been—Eliza Ashworth.

I stepped back, my mind reeling. It was impossible. It was insane. Yet here was the proof, standing before me, defying everything I knew of medicine, of science, of the natural order of things.

On a shelf near the door, precisely where Thorne had said it would be, sat a mantel clock. I moved towards it as if in a trance. The case was rosewood and brass, the face white enamel painted with delicate forget-me-nots. It was beautiful, and it was not running. The hands were stopped at midnight.

I turned it over with shaking hands. On the back panel, I found a small catch, cunningly concealed. It opened to reveal the mechanism within—gears and springs of extraordinary complexity and precision. And there, gleaming in the lamplight, was a small lever wrought in silver.

It was set in what I presumed to be the locked position.

I stood there for an eternity, or perhaps only a moment—time itself seemed uncertain in that room. I thought of Thorne’s warning, his fear of what might happen when the mechanism was released. I thought of Lord Ashworth, dead now, having spent forty years grieving his lost daughter. I thought of Eliza herself, trapped here in this single instant, neither alive nor dead, conscious or unconscious, caught in a space between moments.

And I thought: Who am I to leave her here? What right have I to keep her in this prison, however fearful I might be of the consequences of release?

I reached out and turned the lever.

For a heartbeat, nothing happened. Then the clock chimed—once, twice, continuing until it had rung out twelve times for the midnight hour it showed. And in the mirror, I saw Eliza Ashworth’s reflection blink.

She drew in a breath—a great, gasping breath, as though she had been drowning and had finally broken the surface. Her hands completed their motion, unfastening the necklace. She lowered them, the jewellery clutched in her fingers, and turned slowly from the mirror.

When she saw me, her eyes widened. She opened her mouth to speak, but no words came. Instead, her face contorted in confusion, then horror, then pain. Her hand went to her throat, her chest, as though she could not breathe. Her skin, which had been pale and perfect, began to change. Not aging, not decomposing, but shifting in some fundamental way, as though the forty years she had lost were catching up not to her body but to her very essence.

“Please,” she whispered, and her voice was young, terrified. “Please, what is happening?”

I stepped towards her, instinct overcoming fear, but she held up her hand to stop me. She was looking past me now, at something I could not see, her expression transforming from terror to wonder.

“Father?” she whispered. “Father, is that you?”

I turned, but there was nothing there—only the empty doorway, the workshop beyond. When I looked back at Eliza, she was smiling through tears, her face radiant with joy and relief.

“I’m coming,” she said, to whoever or whatever she alone could see. “I’m coming, Father.”

She took a step towards the door, then another. And as she walked, she began to change. Her form grew lighter, more translucent, as though she were becoming mist or moonlight. The white nightgown seemed to glow with its own luminescence. She raised her hands before her, and I saw they were fading, dissolving like morning fog beneath the sun.

She paused at the threshold and turned back to look at me. For a moment, our eyes met, and I saw in hers such profound gratitude, such relief at being released from her long imprisonment, that I felt tears spring to my own eyes.

“Thank you,” she said, though her voice seemed to come from very far away, from somewhere I could not follow.

And then she was gone.

Not dead—at least, not in any way I understood death. Simply gone, as though she had stepped through the doorway not into the workshop but into some other realm entirely. I stood there, staring at the empty space where she had been, my heart hammering in my chest, my mind unable to comprehend what I had witnessed.

I do not know how long I remained in that room. Eventually, I became aware that I was holding something. I looked down and saw that I still clutched the clock, its mechanism now silent, the lever in its released position. The painted forget-me-nots seemed to glow in the lamplight.

I returned upstairs on unsteady legs. The house was quiet, Mrs Hadley still asleep in her room. I went to Thorne’s bedchamber, thinking I might sit with him awhile, collect my thoughts before I faced the world again.

He lay as I had left him, eyes closed, hands folded on his chest. Dead. I had pronounced him so myself. But as I approached the bed, I saw something that stopped my heart.

His eyes opened.

Not slowly, not with any sign of returning consciousness—simply opened, fixed upon the ceiling, wide with some emotion I could not name. Terror? Longing? Both at once?

I rushed to his side, reached for his wrist to check for a pulse. But the skin beneath my fingers was cold, and there was no beat of blood, no breath, no sign of life. Yet his eyes remained open, staring, and as I looked into them, I saw they were not the vacant gaze of death but something worse—awareness, consciousness, trapped behind glass.

And then I understood.

She had passed it to him. Whatever property of the suspended state had held her, whatever strange physics had kept her caught between moments—she had transferred it to him in that final touch, that moment when she had been neither fully one thing nor another. He was held now, not in time but in death itself, conscious but unable to move, unable to speak, unable to die properly.

I stumbled back from the bed, horrified. His eyes moved—just slightly, but enough that I knew he saw me, knew me, understood his situation. And there was such agony in that gaze, such pleading, that I nearly ran from the room.

But I am a physician. I am trained to ease suffering, to do no harm. And so I tried everything I knew. I attempted to close his eyes, but they remained open. I checked again and again for any sign of life that might be revived, but there was none. He was dead by every measure I possessed, yet those eyes continued to stare, continued to plead.

At last, as dawn broke through the window, I knew there was nothing I could do. Nothing medical science could do. He was trapped as Eliza had been trapped—but where she had been released into whatever peace awaited her, he had been imprisoned in his final moment, in his aged and diseased body, in pain and fear and understanding of what he had done.

I told Mrs Hadley that he had died in the night, that he had gone peacefully. I signed the death certificate and arranged for the undertaker. And when Thorne was buried three days later in the cemetery at St James’s, I alone knew that he was not at rest, that he had been placed in the ground conscious, aware, unable to scream or struggle or beg for mercy.

I pray his soul has since departed, though I do not know if it can. Perhaps he remains there still, trapped in that darkness, alone with his guilt and his punishment for however long eternity lasts.

I have written this account in full, though I know it sounds like madness. I have included every detail I can recall, every word spoken, every sensation felt. I have checked it three times for accuracy, and I swear upon everything I hold sacred that it is true.

I will seal this letter now and place it in my safe, where it will remain until my death. Perhaps some distant descendant will find it amongst my papers and think me mad. Perhaps that is for the best. But I have kept my promise to record what occurred, even if I will never speak of it, never seek to explain or justify or understand.

There are things in this world that lie beyond our comprehension, mechanisms that operate according to laws we cannot grasp. Josiah Thorne discovered one such thing and used it for his own gain, then for his own obsession. And in the end, it destroyed him more completely than any disease or disaster could have done.

I think sometimes of Eliza’s face as she walked towards that doorway, the joy and relief in her eyes as she saw her father waiting. I hope she found peace, hope she was reunited with those she loved, hope the forty years she lost were restored to her in whatever realm she entered.

And I think of Thorne’s eyes, staring up from his deathbed, conscious in death, aware of every moment of his eternal punishment. I pray for his soul, though I do not know if prayers can reach where he has gone.

I have told no one of this, and I never shall. This letter will be my only testimony, my only confession. When I am gone, let whoever finds it judge me as they will for what I did that night in the workshop, for turning that lever, for releasing Eliza Ashworth from her prison.

I believe I did the right thing. But I will carry the memory of Thorne’s eyes—pleading, terrified, conscious—to my own grave. And I will wonder, always, whether mercy and justice are the same thing, or whether in serving one, I betrayed the other.

May God have mercy on all our souls.

Dr Edward Chenowith

London

December 1888

THE END

Leave a comment