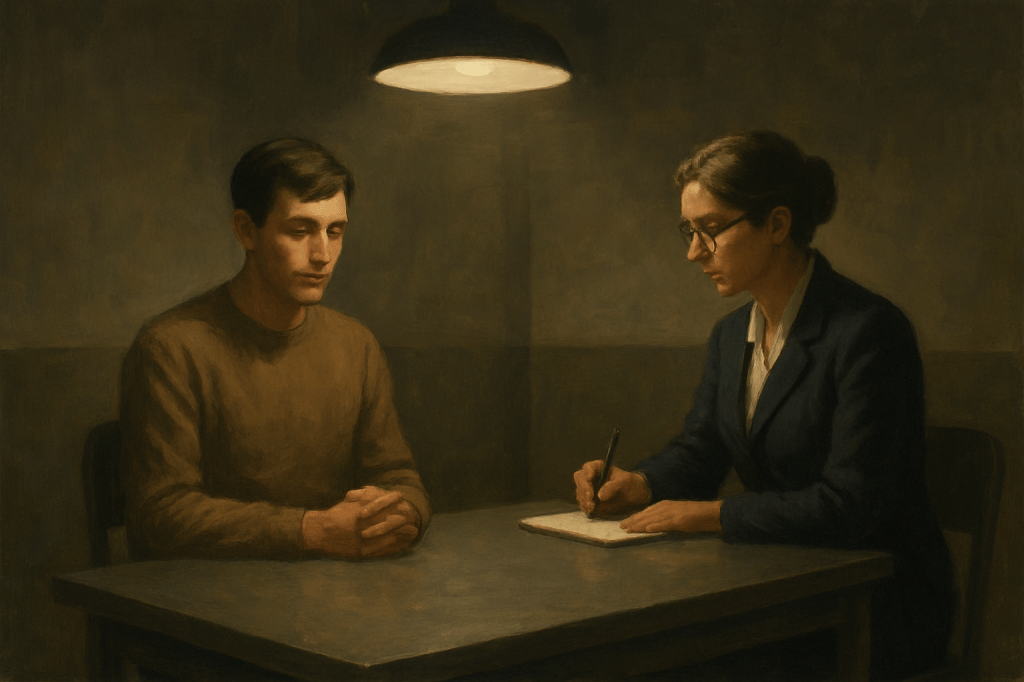

The interview room is cold, though I am used to it. Chill air, hard chairs, the scrape of a pencil—such things become part of one’s day. The Doctor sits opposite, her notes aligned as if order might shield her. She adjusts her spectacles though they do not need adjusting. I give her my best manner: back straight, hands folded, a polite smile. One must make a good impression.

“You’ve been here some years,” she begins. “I think it would help us if you spoke about your childhood.”

My childhood? Ordinary enough. My father was a butcher and I spent much of my youth in his shop. The walls were whitewashed brick, the air sharp with sawdust and blood, the floor always damp. Father kept his knives in order, each in its place. He had no patience for waste and none at all for a careless hand.

I remember watching him bleed a pig for the first time. I was small enough to stand beneath his arm, looking upward. He worked with one smooth cut and the blood fell into the trough with a sound like warm rain. I was not frightened. I was fascinated. There was a rhythm to it: the stillness before, the motion itself, then silence. Life, then no life, all within seconds.

“Most children look away,” he said quietly, not stopping his work. “But you’re watching every movement, aren’t you?” His voice held approval, but also something calculating. “That’s good, boy. Very good indeed.”

The Doctor looks at me over her spectacles. Her pen hesitates, the tip resting on the page. “And how did you feel, helping him?”

Feel? It was a skill. No different from arithmetic or penmanship. My father valued precision above all. A wrong cut wastes meat. A trembling hand spoils the joint. He would say, “Steady now, boy. A precise stroke saves trouble later.” Sometimes, when I worked particularly well, I caught him watching me with an expression I couldn’t quite read. Satisfaction, certainly. But something else. Something that suggested he saw more in my steady hands than mere butchery skills.

I practised until I could separate flesh from bone in a way that pleased him. He praised me. “You’ve the makings of a master, lad.” Those words mattered more to me than anything my schoolteacher ever said.

The Doctor writes something down. “Do you remember the first time you harmed an animal on your own?”

Ah. Yes. The dog. Not ours—a stray, a ragged thing that haunted the yard. I was twelve, perhaps thirteen. Father had been gone three days on business. The shop felt different without his presence—emptier, yet also full of possibility. I found myself studying his knives more carefully, testing their weight in my hand. The precision he demanded seemed less important than the power they represented.

That’s when I noticed the dog watching me through the window, as if it sensed something had changed.

I wanted to test myself, to prove his lessons had taken root. I coaxed it close with scraps. It trusted me easily; dogs will, if you are patient. My hand was steady. The blade went in clean.

What I felt was satisfaction. Not the bloody satisfaction one might expect, but something cleaner. The satisfaction of a job done properly. Of proving Father’s lessons had taken root. I had been steady. I had been precise. For the first time, I understood what mastery felt like.

When I looked up, Father stood in the doorway. He’d returned early, he said, but something in his manner suggested he’d been watching longer than he admitted. “Well done, boy,” was all he said. But his smile was the proudest I’d ever seen.

The Doctor’s pencil stills. She glances up quickly, then down again. “Your father… he knew about the dog?”

He cleaned up afterwards. Told me where to bury it. Said these things happen, that I shouldn’t trouble myself about strays. He also mentioned that I was ready for more responsibility. That perhaps I could mind the shop alone more often.

Her pencil stops entirely. I see understanding dawn—that I wasn’t a boy who went wrong, but one who was carefully cultivated.

She clears her throat. “And people? When did that begin?”

Later. I was nearly grown. By then Father trusted me with the shop in his absence. I could dress carcasses alone, break down sides without error. Once you’ve worked that way, you begin to see how little separates pig from man. Truly, it is not such a great leap.

I recall one man—a drifter. No fixed abode, no family to speak for him. He drank gin and slept rough. People spoke of him as a nuisance.

“The drifter wasn’t random, was it?” she asks quietly.

Father mentioned him often. Said the man was becoming troublesome, bothering customers. One evening, he suggested I handle it while he visited his sister in the next village. He even suggested which knife would be most efficient.

When the man vanished, no one raised an alarm. “Good riddance,” I heard a woman say. But I knew where he had gone. I had made sure of it, just as Father had taught me to make sure of everything.

The Doctor looks up sharply, then smooths her expression. “You understand these… actions… were wrong?”

So I am told. Yet wrong is not the word I would have used at the time. Efficient, perhaps. Necessary. A steady blade is always preferable to a trembling one. Surely, Doctor, you of all people appreciate precision?

Her pen halts mid-stroke. The silence stretches. I let it. Silence has its uses.

At last she says, “Why share this with me now?”

Because you asked. And because I am transparent. I am not a monster raving at the walls. I am a man who has considered his past. A man who has learned. Father always said that good work deserves recognition. He’d be proud to know I’m finally getting the acknowledgement I deserve.

I lean forward slightly. “You see, Doctor, I wasn’t a disappointment to my father. I was his greatest success.”

I fold my hands a little tighter, give her the faintest smile.

She writes again, slowly, the nib of her pen scratching as though reluctant to form the words. Her expression is careful, too careful—but I see the smallest nod, the hint of concession. She is listening. That is all I require—to be listened to, to be believed.

I have learned patience. I can wait. A steady hand, Father said, saves trouble later.

Soon I might be able to continue the family business. I believe I am quite ready to go home, Doctor. Quite ready indeed.

Leave a comment