When Henry Slesar’s Examination Day appeared in Playboy magazine in February 1958, readers thought they’d be getting a straightforward coming-of-age story about a boy’s first intelligence test. By the final paragraph, they’d been gut-punched by one of sci-fi’s most devastating reversals. In just 1300 words Slesar created a masterclass in misdirection that still leaves us reeling nearly seventy years later.

The story follows 12-year-old Dickie Jordan on his birthday, as his anxious parents prepare him for the mandatory Government Intelligence Test. What begins as typical parental worry about their child’s performance transforms into something far more sinister when we discover the true purpose of the exam.

Stop Right Here

If you haven’t read “Examination Day,” stop now and read it (about a 6-minute read). This analysis does contain spoilers, including the story’s shocking conclusion and the mechanisms Slesar uses to manipulate our expectations so brilliantly.

The Art of Double Misdirection

Slesar opens with a birthday celebration. Presents, cake, parental affection: all the trappings of childhood milestone stories. The “exam” feels like a school test. Nothing life-changing, but something parents do worry about. We’re primed to read this as a tale about academic pressure or childhood anxiety.

But Slesar plants his clues in plain sight. The parents “never spoke of the exam” until Dickie’s twelfth birthday. His mother’s “anxious manner” and “moistness of her eyes” suggest something beyond normal parental concern. The father’s sharp responses to Dickie’s curious questions feel defensive, even protective.

When Dickie asks why it has to rain on his birthday, his father snaps that “nobody knows” why grass is green. Later, when the boy wonders how far away the sun is, his father answers: “Five thousand miles.” Do these responses reveal a desperate man trying to dampen dangerous curiosity, or someone whose own intelligence is limited?

The Totalitarian Mundane

Slesar’s dystopia feels terrifyingly plausible because it operates through bureaucratic efficiency rather than dramatic oppression. The Government Educational Building with its “marble floors” and “great pillared lobby” suggests institutional respectability. The testing procedure feels clinical: forms to fill out, numbers to check, scheduled appointments.

The truth serum (disguised as peppermint-flavoured drink) reframes everything we thought we understood. Truth serums suggest lies and secrets, yet what secrets could a twelve-year-old boy possibly harbour? The answer, of course, is that his only secret is his intelligence itself.

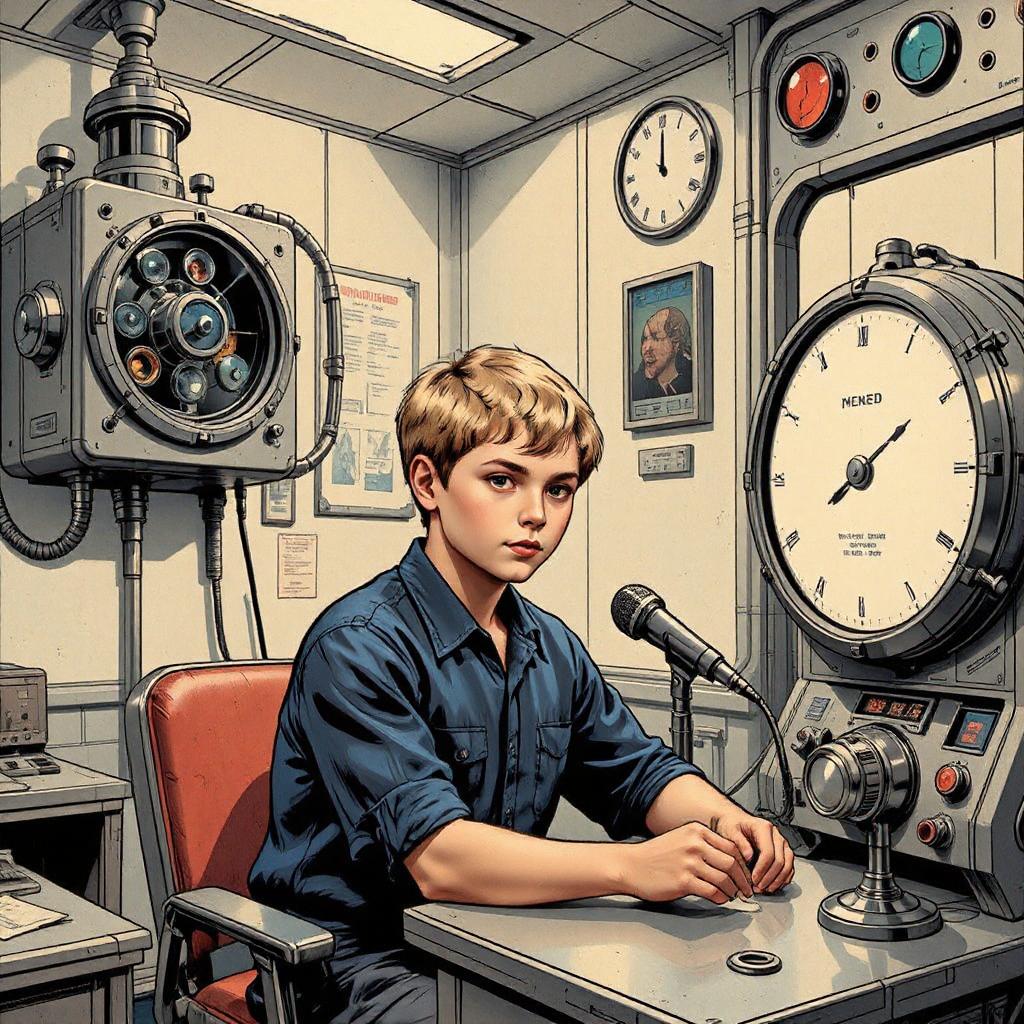

The testing room with its “multi-dialled computing machine” and microphone setup feels almost benign. “Now just relax, Richard. You’ll be asked some questions, and you think them over carefully.” It does sound like every standardised test ever administered.

The Killer Revelation

The phone call that ends the story represents bureaucratic horror at its most chilling:

“We regret to inform you that his intelligence quotient is above the Government regulation, according to Rule 84 Section 5 of the New Code.”

The language is perfectly bureaucratic: formal, apologetic and matter-of-fact. The caller might be informing the Jordans about a parking violation. The casual inquiry about burial preferences (“The fee for Government burial is ten dollars”) adds insult to injury.

The horror is in the routine organisational procedures. Instead of political persecution, we’re presented with administrative housekeeping. The government processes intelligent people efficiently rather than hating them.

Why the Twist Devastates

Slesar’s genius lies in weaponising our own values against us. We want Dickie to be smart. We root for his curiosity when he asks about rain and grass and distant suns. Intelligence represents everything we value: potential, progress, hope for the future.

The story works because it contains not one twist but two:

First inversion: the test identifies intelligence for elimination rather than rewarding it.

Second inversion: The government eliminates the gifted rather than the “unfit”. The bright children die, while the stupid ones live.

This double reversal exploits both our cultural conditioning (intelligence = success) and our dystopian fiction expectations (totalitarian regimes eliminate the weak, not the strong). We’re looking in completely the wrong direction, which makes the revelation even more shocking.

The Parents’ Impossible Position

The story’s cruellest element might be the parents’ helplessness. They know what’s coming but cannot prevent it. Worse, they cannot even warn Dickie because his natural responses to the test questions will determine his fate.

Their love for his curiosity becomes complicit in his death. Every encouraging word about his intelligence, every answered question, every moment of parental pride has been unwittingly preparing him for execution.

The father’s wrong answer about the sun’s distance becomes even more chilling when we consider it might reflect genuine ignorance rather than protective deception. If he truly doesn’t know, it suggests the system has already succeeded in creating a population where only the intellectually limited survive to reproduce. Dickie’s curiosity and intelligence become remarkable precisely because he’s growing up in a world where such traits have been systematically eliminated.

A Nightmare That Feels Possible

“Examination Day” endures because Slesar understood something fundamental about authoritarian control: effective oppression operates through our existing institutions. Schools, tests and bureaucracy. These familiar systems become instruments of terror through subtle redirection.

The story anticipates concerns about standardised testing, government surveillance, and the weaponisation of education that feel remarkably contemporary. In our age of data collection and algorithmic assessment, Slesar’s vision of a state that fears citizen intelligence seems less like science fiction and more like reality.

The Perfect Short Story

“Examination Day” demonstrates everything a great short story can achieve. In barely 1300 words, Slesar creates a complete world, develops authentic characters, builds emotional investment and delivers a twist that recontextualises everything we thought we understood.

The story doesn’t waste a word. Every detail serves multiple purposes: building atmosphere, developing character and laying groundwork for the devastating conclusion. The birthday setting provides false comfort, the parents’ anxiety creates dread and Dickie’s curiosity becomes both endearing and ominous.

Most importantly, Slesar understood that twists work most effectively when they create a horrible new sense out of everything that came before, rather than simply surprising us. The parents’ behaviour, the bureaucratic efficiency and the clinical testing procedures all make perfect, if terrible, sense once we understand the government’s true purpose.

Why It Still Works

Nearly seventy years later, “Examination Day” remains as shocking as ever because it taps into primal fears about the people we trust. Teachers, administrators and governments. The very institutions meant to nurture and develop our children’s minds.

Slesar created a story that seems to be about one thing (academic anxiety) while actually exploring something much darker (state control through fear of citizen intelligence). He showed that the most effective horror is concealed under the cloak of helpful bureaucracy, rather than announcing itself with fanfare.

In our current era of surveillance and schools’ data-driven assessment, “Examination Day” feels less like a vintage sci-fi tale and more like a warning we should have heeded. Really frightening futures are the ones where all our systems work exactly as designed… just not for the purposes we thought.

Leave a comment