Step into The Gothic Hour, where shadows grow longer and the past refuses to stay buried! These stories draw from the rich tradition of classic horror. Think creaking floorboards, ancient curses, and secrets that span generations, while keeping one foot firmly planted in the modern world. Here you’ll find cursed heirlooms in contemporary homes, museum artefacts with malevolent intentions, and family legacies that refuse to die. Here, we’re not interested in cheap thrills or gore. Instead, The Gothic Hour offers the slow-burning dread that made writers like Poe and M.R. James masters of their craft. These are stories that understand the most terrifying horrors often wear the mask of respectability, hiding in plain sight until the moment they reveal their true nature.

The Old Bed

Julian Ashworth counted the coins in his palm for the third time that morning. Two shillings and fourpence. Enough for bread, perhaps, but not bread and lodging. The eviction notice lay crumpled on his table beside yesterday’s cold tea, and he had seven days to find somewhere else to sleep.

The knock at his door came with the solemnity of fate itself.

“Mr Ashworth? I’m Grimsby, solicitor to the late Cornelius Ashworth.” The thin man peered over wire spectacles. “I’m afraid I have news of a death in the family.”

Julian’s great-uncle had been a stranger to him, known only through whispered family stories of cruelty and avarice. A man renowned for dismissing servants without wages, who had driven away beggars from his door in the cruellest of winters, who had passed from this world utterly alone and unmourned in his crumbling estate.

“And no doubt you are sorry for my loss,” said Julian, who, for his own part, felt nothing of the sort.

“Yes, well.” Grimsby consulted his papers. “The matter at hand is your inheritance. As his only living relative, you are to receive Ravenshollow House and its contents.”

Julian’s heart leapt! A house. A roof. Deliverance.

“However,” Grimsby continued, “I am tasked to present you with this letter, written in your uncle’s hand shortly before his passing.”

The paper was thick and expensive, and bore the unmistakable spidery script of Great-Uncle Cornelius:

To whomever would claim that which is mine:

This house belongs to me, and to me alone. With my final breath I bind my spirit to these walls, that I might guard what is rightfully mine for all eternity. Let no other seek to dwell here, for I shall not suffer an usurper to live. Whomsoever sleeps beneath this roof for three nights shall know madness, and in madness shall know the true master of Ravenshollow House.

I have spoken it. I have willed it. It shall be.

—Cornelius Ashworth

Julian read it twice, then looked up to find Grimsby watching him carefully.

“Dramatic fellow, wasn’t he?” Julian folded the letter. “When might I take possession?”

“You are not… concerned by the contents of the letter?”

“Mr Grimsby, I shall be sleeping in doorways within the week. If my uncle’s ghost wants to contest the inheritance, he’s welcome to try.” Julian stood, already in his mind packing what few belongings he possessed. “The keys, if you please.”

Ravenshollow House squatted against the grey October sky like a wound in the landscape. Its windows were dark, its grounds overgrown and ivy crawled across its facade with the patience of decades. Julian stood at the rusted gate, carpet bag in hand, and felt the first whisper of unease.

The house was larger than he’d imagined, and in a somewhat worse state of repair. Shutters hung at drunken angles, roof tiles lay scattered in the weeds, and the front steps sagged beneath their burden of neglect. That said, it had walls and a roof, which was more than Julian had possessed earlier that morning.

The key turned with reluctance, and the door opened on a tomb-like silence.

Empty! Completely, utterly empty.

Julian’s footsteps echoed through rooms stripped of everything valuable. Rectangles of cleaner wallpaper marked where paintings had hung. Indentations in dusty floors showed where furniture had stood. The auction house had certainly been thorough—not even the light fittings remained.

He climbed the stairs, fingers trailing on a banister worn smooth by generations of Ashworth hands, and found the same emptiness on the first floor. Bare rooms, bare windows, bare boards.

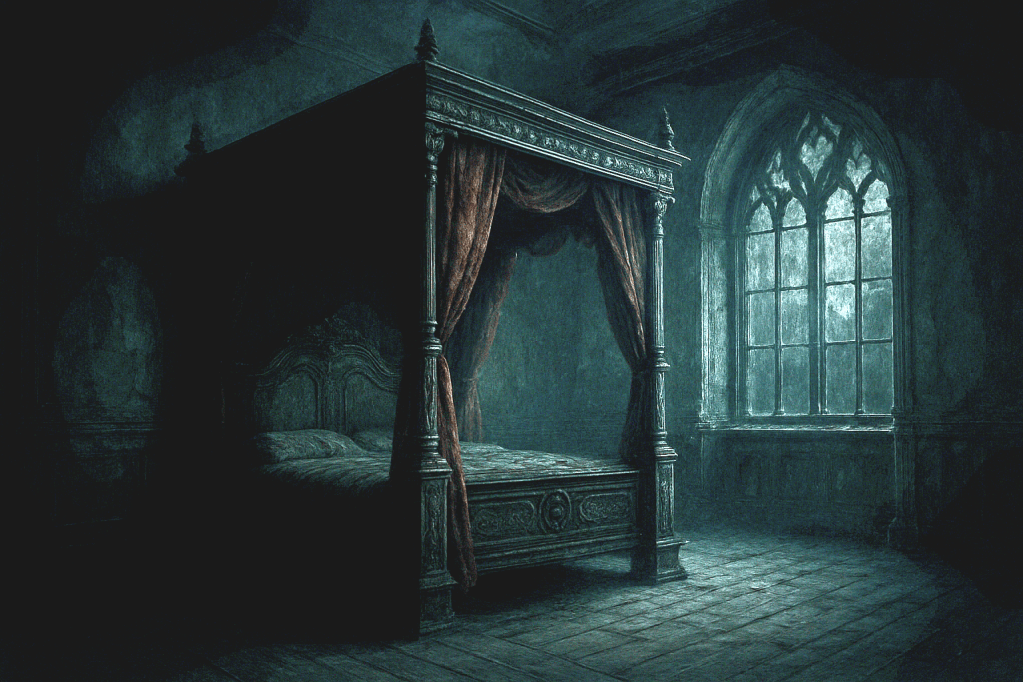

But in the master bedroom, at the far end of the corridor, something waited.

A bed.

It was a massive thing, carved from dark oak that seemed to drink in the pale afternoon light. Its posts rose like cathedral pillars, supporting a canopy of faded burgundy curtains. The mattress sagged in the middle, and the whole structure had an air of great age and greater malevolence.

A note lay on the pillow, written in the same spidery hand:

They took everything else, but this they would not touch. Even the auction men crossed themselves and walked away. Perhaps they were wiser than you.

Julian crumpled the note and stuffed it in his pocket. Superstitious fools, the lot of them! A bed was a bed, and he’d been sleeping on boards for too long to be particular.

As evening fell and shadows gathered in the empty house, Julian lit a candle and climbed between the musty sheets. The mattress was surprisingly comfortable, moulding itself to his body as if it remembered the shape of flesh and bone.

Sleep came quickly in that soft embrace.

And with sleep came the dreams of Cornelius Ashworth.

The First Night

In the dream, Julian stood in the same bedroom, but it was transformed. Rich tapestries adorned the walls, and candles flickered in silver sconces. The bed beneath him was draped in silk, not the threadbare coverings he had pulled over himself. He wore not his own patched nightshirt, but a gentleman’s nightgown of finest cambric.

A servant cowered before him—a thin, frightened girl clutching a pewter candlestick.

“Please, sir,” she whispered, “my mother is dying. I only ask for a day’s leave to tend her.”

Julian opened his mouth to grant the request, but different words emerged, spoken in a voice rougher than his own: “Your mother’s ailments are not my concern. You were hired to serve this house, not to abandon your duties at every trifling complaint.”

“But sir, the physician says—”

“The physician may say what he pleases. You will remain at your post, or you will find yourself without employment before dawn.” The words tasted bitter on Julian’s tongue, yet he could not stop them. “Now leave me before I am forced to dock your wages for your impertinence.”

The girl fled, sobbing. Julian tried to call after her, to apologise, but his throat would not obey. Instead, he found himself smiling—a cold, satisfied expression that belonged to another man entirely.

The dream shifted. Now he sat at a grand dining table, silver gleaming in the candlelight. A knock came at the door, and the same frightened servant girl appeared.

“Begging your pardon, sir, but there’s a family at the door. Says they’ve nowhere to sleep, and with the snow falling…”

Through the tall windows, Julian could see the storm—great white flakes swirling in the darkness beyond the warm glow of the dining room. He thought of the woman and children he had glimpsed through the frosted glass, their threadbare coats insufficient against the bitter wind.

“Turn them away,” came his voice, though his heart cried out in protest. “This is not a workhouse. If they cannot afford proper lodgings, that is their misfortune, not mine.”

“Sir, the little ones—”

“Are no concern of mine.” The voice grew sharper, more imperious. “Bar the door and draw the curtains. I will not have beggars spoiling my supper!”

Julian watched his hand reach for the wine glass, saw himself drink deeply whilst beyond the windows, shadows moved away into the storm. He tried to rise, to run after them, but his body would not respond. He was a prisoner in his own flesh, forced to witness cruelties he would never have committed.

The dream fragmented into smaller scenes: refusing a loan to a desperate tenant whose crop had failed, dismissing a servant for the crime of growing old, turning away a physician who begged him to sponsor care for the village’s poor children. Each act of callousness felt both alien and familiar, as if Julian were remembering sins he had never committed.

When he woke, grey dawn was seeping through the grimy windows. For a moment, Julian lay still, the taste of dream-wine sour in his mouth. The images remained vivid—more vivid than any dream he had ever experienced. He could still feel the weight of that strange nightgown, still smell the candle wax and silver polish.

He rose and dressed quickly, eager to escape the oppressive atmosphere of the bedroom. But as he descended to the empty kitchen in search of water, he caught himself humming a tune he did not recognise—a slow, melancholy air that seemed to belong to another century.

Outside, rain drummed against the windows with cold persistence, and Julian found himself thinking that any traveller caught in such weather deserved whatever fate befell him. The thought came unbidden, unwelcome, and he shook his head to clear it.

Just a dream, nothing more. The curse was mere superstition, and dreams were simply the mind’s way of processing the strange events of the day.

But as the morning wore on, Julian found himself humming that unknown melody again and yet again, as if it had taken root in some deep corner of his soul.

The Second Night

Julian had intended to stay awake. He fashioned a makeshift chair from his carpet bag and positioned himself by the window, determined to prove that whatever strange influence plagued this house could not touch a man who refused to sleep. But the ancient bed seemed to exert a peculiar magnetism, drawing his gaze over and over to its shadowed depths.

By midnight, his eyelids grew heavy. By one o’clock, his resolve had crumbled entirely.

This time, the dreams began before he had fully settled into sleep.

He stood in the entrance hall of Ravenshollow House as it had been in its prime—polished marble floors gleaming beneath crystal chandeliers, portraits of stern ancestors gazing down from gilded frames. But now Julian was no mere observer; he inhabited the dream completely, his consciousness merged with that of his great-uncle.

The young man knelt before him—scarcely more than a boy, with callused hands and desperate eyes.

“Please, Mr Ashworth,” the youth pleaded, “my father borrowed the money in good faith. The harvest failed through no fault of ours. Give us another season, and we’ll repay every penny with interest.”

Julian felt his mouth curve into a smile that was not his own, though it felt terrifyingly natural. “Your father’s misfortunes are of no concern to me. The debt is due today, as stipulated in our agreement.”

“But sir, if you foreclose on the farm, we’ll have nothing. My mother, my sisters—”

“Then perhaps they should have considered that before your father chose to gamble with money that was not his.” Julian’s voice carried a satisfaction that made his sleeping conscience recoil. “The constables will arrive at dawn to remove you from the property. I suggest you spend your remaining hours gathering what possessions you can carry.”

The boy’s face crumpled. “You’re condemning us to the workhouse. My youngest sister is but seven years old—”

“The workhouse exists for those too feckless to provide for themselves.” Julian waved a dismissive hand, and the gesture felt like his own muscle memory. “Perhaps the experience will teach your family the value of industry and thrift.”

The dream dissolved and reformed. Now Julian sat in his study, reviewing ledgers by lamplight. Each entry told a story of human misery: tenants evicted for late payments, servants dismissed without references, loans called in at the most inconvenient moments. But rather than feeling revulsion, Julian found himself admiring the neat columns of figures and the methodical accumulation of wealth.

A soft knock interrupted his calculations. The frightened servant girl from the previous night’s dream appeared in the doorway, her face hollow with grief.

“Sir,” she whispered, “I must tell you—my mother passed in the night. Without the physician’s care you forbade me to seek…”

Julian looked up from his ledgers with irritation. “And you disturb me with this news because…?”

“I… I thought you should know, sir.”

“What I should know,” Julian said, rising from his chair with fluid authority, “is why you imagine your personal tragedies are of any interest to me. Your mother’s death changes nothing—you will continue your duties as before, and I’ll hear no more snivelling about your loss.”

The girl’s eyes filled with tears, but she curtsied obediently. “Yes, sir.”

“Furthermore,” Julian continued, surprising himself with the casual cruelty of his words, “your distraction over this matter has led to substandard service. Your wages for this month are forfeit.”

“But sir, how shall I pay for the burial—”

“That is not my concern. Now remove yourself from this room before I decide you to be more trouble than you’re worth.”

When the girl had gone, Julian returned to his ledgers with perfect satisfaction. The numbers swam before his eyes, but each figure represented power, control and the delicious ability to shape lives according to his will.

The dreams continued through the night—a parade of victims, each encounter more vindictive than the last. Julian watched himself foreclose on a widow’s cottage in winter, refuse medicine to a sick child whose parents owed him money, dismiss an elderly gardener who had served the family for forty years. With each act of cruelty, the boundaries between his own consciousness and that of his great-uncle grew more blurred.

When morning came, Julian woke with a sense of profound satisfaction that took several minutes to fade. The grey light filtering through the windows seemed harsh and unwelcome after the warm glow of the dream-world candles. He dressed slowly, his movements carrying an unconscious authority that had not been there the day before.

In the empty kitchen, he found a letter that must have been slipped under the door during the night. His name was written on the envelope in an educated hand.

Mr Ashworth,

I am the vicar of St Michael’s in the village. Word has reached me of your arrival at Ravenshollow House. Might I call upon you this afternoon? There are matters of charitable concern that your late uncle’s passing has left unresolved, and I should be grateful for your counsel.

Your servant, Reverend Blackwood

Julian read the letter twice, and with each reading, his expression grew colder. Charity—that eternal burden placed upon those of means by those without. No doubt the good reverend expected him to honour whatever foolish commitments Cornelius had made to the local poor.

He took up his pen and wrote his reply in handwriting that seemed to flow with practised authority:

Reverend Blackwood,

I fear you mistake me for a man of philanthropic disposition. My uncle’s charitable obligations died with him. I have no intention of subsidising the indolence of the local population.

Do not trouble yourself to call.

J. Ashworth

It was only after he had sealed the letter and dispatched it with a passing boy that Julian realised what he had done! The words on the page might have been his own hand, but they carried the voice of another man—a man he was resembling more with each passing hour.

He spent the rest of the day walking the grounds of Ravenshollow House, finding himself noting improvements that could be made, tenants who might pay higher rents and land that could be enclosed for profit. The thoughts came as naturally as breathing, though he could not remember ever having such inclinations before.

As evening approached and shadows lengthened across the overgrown gardens, Julian Ashworth felt the familiar pull of the ancient bed. This time, he did not resist.

The Third Night

Julian did not dream at all.

Rather, he… remembered.

He remembered forty years of methodical cruelty, each slight and humiliation carefully catalogued in a mind that had made an art of vengeance. He remembered the exquisite satisfaction of watching hope die in a debtor’s eyes, the delicious power of holding another’s fate in his hands and choosing mercy or destruction on a whim. He remembered the weight of gold in his palms and the lightness of conscience that came from viewing other humans as mere instruments for his pleasure.

These were not dreams now, but his own memories, as vivid and real as his first breath. Julian Ashworth—poor, desperate Julian who had arrived three days ago with nothing but a carpet bag and crumpled eviction notice—was fading like morning mist. In his place sat Cornelius Ashworth, master of Ravenshollow House, who had never truly died at all.

He rose from the bed as dawn broke, his movements carrying the authority of decades. The shabby clothes he had worn hung loose upon a frame that somehow felt broader, more commanding. When he caught sight of himself in the tarnished mirror above the mantelpiece, the face that looked back was his own—yet not. The same features, but aged with cunning and hardened by years of calculated malice.

A knock at the front door.

Cornelius—for that is who he was now, had always been—descended the stairs with measured steps. On the doorstep stood a young woman in a worn cloak, a squalling infant in her arms and two small children clinging to her skirts.

“Please, sir,” she said, her voice barely above a whisper, “we’ve nowhere else to turn. My husband died in the mill accident last month, and the landlord has put us out. If we could just shelter in your stables until—”

“You mistake me for a charitable institution,” Cornelius replied, his voice carrying the polished cruelty of long practice. “This is a private residence, not a refuge for the indigent.”

“Sir, my children haven’t eaten in two days. If you could spare just a crust of bread—”

“What you require,” Cornelius said, examining his fingernails with calculated indifference, “is industriousness, not charity. Perhaps hunger will motivate you to seek proper employment rather than begging at the doors of your betters.”

The woman’s face crumpled. “But the children, sir—”

“Are not my responsibility.” He began to close the door, then paused as if struck by sudden inspiration. “However, I am in need of a scullery maid. The position pays two shillings monthly, with lodging in the cellar. Your eldest daughter appears strong enough for the work.”

The woman clutched her children closer. “She’s but nine years old—”

“Old enough to earn her keep. You may leave her here and remove yourself and the burdens from my property, or you may all depart together. I care not which you choose.”

“Monster,” the woman whispered, backing away. “What manner of creature are you?”

Cornelius smiled, and in that expression lay all the accumulated malevolence of a lifetime. “I am Cornelius Ashworth, and I shall be master of this house for all eternity. Remember that name, and teach your children to fear it.”

He closed the door on their retreating figures and returned to his study—for it was his study now, furnished once again with the phantom objects of memory and will. He took out paper and pen, his hand moving with the fluid confidence of long habit.

The letter he wrote was addressed to no one in particular, but he knew it would find its way to whomever next inherited this house, this bed, this exquisite curse:

To whomever would claim that which is mine:

This house belongs to me, and to me alone. With my final breath I bind my spirit to these walls, that I might guard what is rightfully mine for all eternity. Let no other seek to dwell here, for I shall not suffer an usurper to live. Whomsoever sleeps beneath this roof for three nights shall know madness, and in madness shall know the true master of Ravenshollow House.

I have spoken it. I have willed it. It shall be.

—Cornelius Ashworth

He set down the pen and leaned back in his chair, satisfied. Julian Ashworth was gone—had perhaps never truly existed at all. There was only Cornelius now, eternal and unchanging, guardian of his domain.

Somewhere in the depths of his consciousness, a small voice cried out in horror at what he had become. But it was easily silenced, smothered beneath decades of accumulated cruelty and the intoxicating weight of absolute power.

Outside, winter was coming early to Ravenshollow House. The trees bent beneath bitter winds, and the first snow began to fall—sharp flakes that cut like glass against the windows.

Cornelius smiled and began to plan which tenants he would visit come the morning. After all, rents were due, and he had been absent from his duties for far too long.

The old bed waited in the master bedroom, its dark wood gleaming with malevolent satisfaction. Soon enough, another desperate heir would arrive, drawn by necessity to claim what they believed to be their salvation. And when they did, Cornelius Ashworth would be ready to welcome them home.

Leave a comment