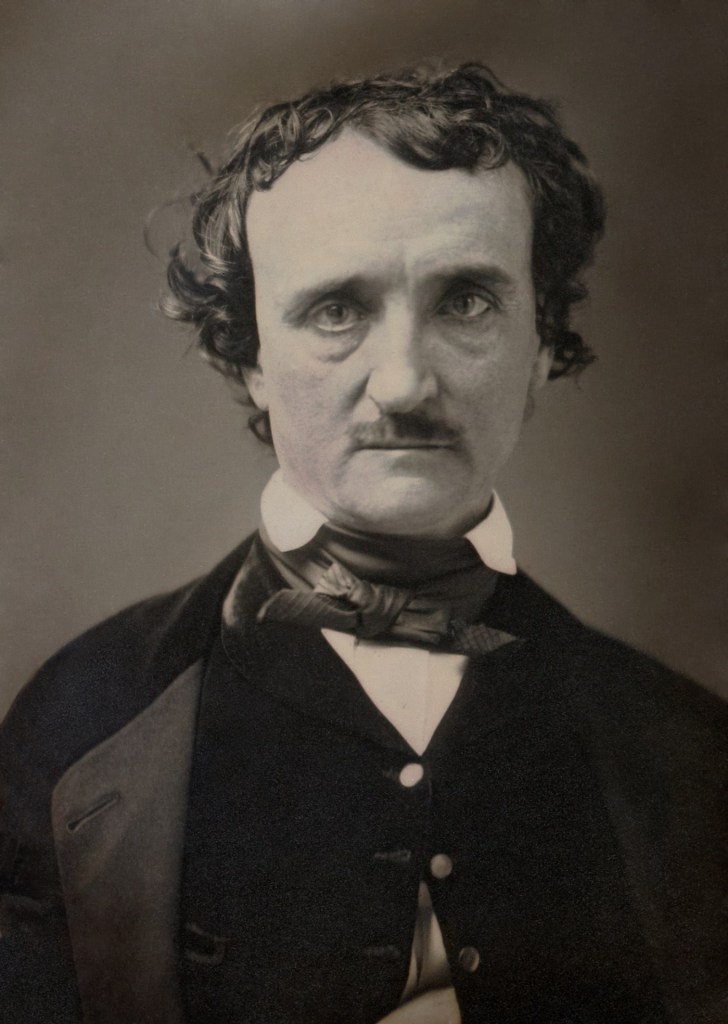

When Edgar Allan Poe published The Oval Portrait in 1842, he created one of literature’s most chilling meditations on art, obsession and the price of creation. In fewer than 1,500 words, Poe crafted a story that asks whether art can literally steal life from its subjects. The answer he provides is both beautiful and horrifying.

This tale of a painting that seems more alive than its long-dead subject explores the dangerous relationship between artist and muse, between creation and destruction. The result is a perfect gothic horror that reveals how the pursuit of artistic perfection can become a form of murder.

Stop Right Here

If you haven’t read The Oval Portrait, stop now and read it. At roughly 1,400 words, it’s about a six-to-eight-minute read. This analysis discusses the story’s shocking revelation about the painting’s creation and the fate of its subject. I’d hate to spoil Poe’s masterful twist!

The Frame Within the Frame

Poe opens with an injured narrator taking refuge in an abandoned chateau. Unable to sleep, he discovers a volume describing the paintings that cover the walls. The setup feels almost casual: a wounded traveller, some old art, a book of explanations.

Yet Poe immediately plants seeds of unease. The chateau is “one of those piles of commingled gloom and grandeur.” The paintings hang in “the deep recesses” of the building. Everything suggests decay, abandonment, secrets waiting to be uncovered.

The narrator’s condition adds to the atmosphere. He’s wounded, feverish and possibly unreliable. His perception might be compromised by injury and medication. Poe uses this uncertainty to blur the line between reality and hallucination, making us question what we’re actually seeing.

The Living Portrait

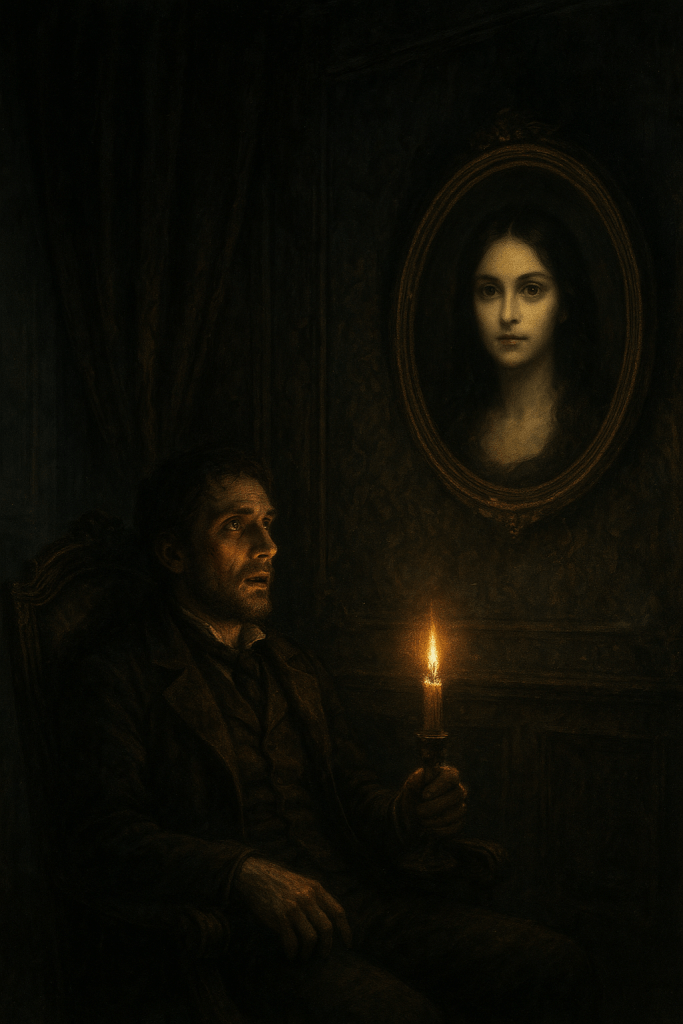

When the narrator discovers the oval portrait, Poe gives us one of literature’s most unsettling descriptions of art imitating life. The painting shows “a young girl just ripening into womanhood” with such lifelike quality that it startles him into full wakefulness.

The portrait’s realism becomes almost supernatural. The narrator notes “the absolute life-likeliness of expression” and how it seems to breathe with actual life. He suggests that great art goes beyond representing reality: it steals reality, captures something essential that belongs to the living world.

The circular frame adds to the portrait’s power. Ovals suggest completeness, eternity and the endless cycle of life and death. The shape contains and concentrates the painting’s supernatural energy, making it feel like a window into another world rather than mere pigment on canvas.

The Nested Horror

He brilliantly structures the story with nested layers. The main narrative becomes a frame for the painting’s true story, which proves far more horrifying than anything the narrator experiences.

Through the book’s account, we learn about the young bride who posed for her artist husband. She “loved and wedded” a man whose only passion was his art. The painting became a competition between husband and wife, between art and life for the man’s devotion.

Poe shows us a marriage destroyed by artistic obsession. The husband sees his wife only as subject matter, material for his masterpiece. She becomes less a person than a collection of visual elements to be captured and perfected.

Art as Vampire

The central horror of the story lies in how the painting literally drains life from its subject. As the portrait becomes more lifelike, the woman grows “daily more dispirited and weak.” The art feeds on her vitality, growing more beautiful as she fades.

Poe presents this exchange as almost mechanical. Each brushstroke removes something essential from the living woman and transfers it to the painted image. The husband, obsessed with his work, fails to notice that he’s killing his wife to create his masterpiece.

The woman’s complicity makes the horror worse. She poses willingly, even lovingly, watching her husband create something more important to him than she is. Her devotion becomes the weapon that destroys her.

The Moment of Completion

The story’s climax occurs when the painter steps back from his finished work and declares it truly alive. At that exact moment, he turns to his wife and discovers she is dead. The painting has absorbed her life completely, leaving only a beautiful corpse.

Poe’s timing is perfect. The moment of artistic triumph becomes the moment of personal tragedy. The husband achieves his greatest work by destroying what he should have treasured most. Success and failure become indistinguishable.

The painter’s reaction suggests he may not even fully understand what has happened. He sees the completed portrait and recognises its perfection, but seems shocked to discover his wife’s death. Art has consumed him as completely as it consumed her.

The Price of Perfection

The Oval Portrait explores the dangerous relationship between artistic ambition and human compassion. The painter’s pursuit of perfect beauty requires the destruction of actual beauty. His masterpiece exists only because his wife no longer does.

Poe suggests that the highest art might demand the highest price. The portrait achieves supernatural realism because it contains something supernatural: an actual human soul. The painter has done more than paint his wife: he’s captured her essence, imprisoned her spirit in pigment and canvas.

The story also examines the role of the muse in artistic creation. The woman enables her husband’s art through her willing sacrifice, yet receives no credit for the masterpiece her death creates. She becomes invisible, remembered as the subject of a painting rather than as a person who lived and loved.

Gothic Economy

The Oval Portrait is remarkable for how much horror Poe achieves with so few words. The story contains no violence, no monsters, no supernatural manifestations beyond the painting’s unsettling realism. The horror emerges from human relationships and artistic obsession.

The writer understood that the most effective horror often comes from ordinary human failings taken to their logical extreme. The painter’s dedication to his art becomes murderous neglect. The wife’s devotion becomes deadly self-sacrifice. Love becomes the instrument of destruction.

The story’s brevity intensifies its impact. Like the painting itself, The Oval Portrait captures maximum life in minimum space. Every word serves the overall effect, creating a perfect example of Poe’s aesthetic theory about unity of impression.

Art and Mortality

This raises uncomfortable questions about the relationship between creation and destruction. Does great art require sacrifice? Can beauty exist without consuming something beautiful? Should artistic achievement matter more than human life?

Poe offers no easy answers. The painting is genuinely magnificent, achieving a kind of immortality that its subject never could. The woman dies, but her image lives forever with supernatural vitality. The husband loses his wife but gains his masterpiece.

Yet the story clearly condemns the painter’s choice. His obsession blinds him to what matters most until it’s too late. He achieves artistic immortality at the cost of human love, creating something beautiful by destroying something irreplaceable.

The portrait serves as a warning about the seductive power of art. It’s so lifelike that viewers mistake it for actual life, just as the painter mistook his artistic vision for something more important than his wife’s actual existence.

Ultimately, and to summarise: what’s on the canvas is beautiful. What’s behind it isn’t.

Leave a comment