The best short stories entertain and challenge assumptions, question authority, and force readers to confront uncomfortable truths. These six stories prove that fiction has real power to disturb, provoke and change minds. Each one sparked outrage, faced censorship attempts or divided readers so sharply that the arguments continue today.

1. “God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian” by Kurt Vonnegut (1999)

Vonnegut’s fictional interviews with recently deceased people seemed like harmless satire. Then they ignited a firestorm about euthanasia, death with dignity and medical ethics. The title alone was enough to send critics into overdrive.

The premise sounds harmless enough. Vonnegut visits the afterlife through near-death experiences, interviewing famous dead people about their lives and deaths. He returns with their wisdom and wit intact. But the Dr. Kevorkian reference wasn’t accidental. Jack Kevorkian was helping terminally ill patients die, sparking national debates about assisted suicide.

Religious groups condemned the stories as promoting suicide. Medical ethicists argued about end-of-life care. School boards debated whether students should read about death so casually discussed. Vonnegut had touched the third rail of American moral debate.

The controversy revealed how deeply uncomfortable we are with honest discussions about mortality. With ongoing debates about assisted dying legislation worldwide, Vonnegut’s gentle humour couldn’t disguise the serious questions underneath. Should people control how they die? Who decides when life is worth living?

2. “The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson (1948)

When this appeared in The New Yorker, readers were furious. Hundreds cancelled subscriptions. Others demanded to know where these lottery towns existed so they could avoid them. Some asked how to participate. Jackson had created something so disturbing that people couldn’t tell if it was fiction or reporting.

A small town gathers for their annual lottery. Everyone participates cheerfully until we discover the “winner” gets stoned to death by their neighbours. Tradition matters more than human life.

Jackson exposed the thin veneer of civilisation. How easily communities turn violent when they follow tradition blindly. How quickly neighbours become executioners. The Holocaust was fresh in readers’ minds, making the story’s themes even more unsettling.

Schools challenged it for violence and dark themes. Parents worried about the psychological impact on children. But Jackson had forced readers to examine their own capacity for cruelty.

3. “The Story of an Hour” by Kate Chopin (1894)

Louise Mallard learns her husband has died in a train accident. After the initial shock, she feels something unexpected: joy. Freedom. Liberation from marriage. Then her husband walks through the door, very much alive. The shock kills her instantly.

Chopin wrote this when women had few legal rights and divorce was scandalous. The idea that a wife might celebrate her husband’s death was unthinkable. Readers were horrified by Louise’s reaction. How could a woman feel joy at such news?

It was banned from anthologies and school curricula for decades. Critics called it immoral, unwomanly, dangerous. Chopin had suggested that marriage might be a prison for women, that freedom might matter more than security.

Today’s readers see Louise’s reaction as tragically understandable. Chopin was ahead of her time, recognising that love and liberation could be incompatible. The controversy persists because it questions whether traditional marriage serves women’s happiness.

4. “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” by Flannery O’Connor (1953)

A family road trip ends in mass murder when they encounter The Misfit, an escaped convict who kills them all. The grandmother tries to save herself by appealing to his religious faith, but he shoots her anyway. O’Connor’s blend of dark comedy and sudden violence left readers reeling.

The story faced challenges for its graphic violence and complex moral themes. Parents objected to children reading about murder so casually depicted. Religious groups disagreed about O’Connor’s theology – was she promoting faith or mocking it?

O’Connor claimed the grandmother experiences genuine grace in her final moments, but many readers see only meaningless brutality. The Misfit’s philosophical discussions about Jesus while committing murder disturbed people who wanted clear moral boundaries.

Schools still debate whether the story’s literary merit outweighs its disturbing content. O’Connor had created something that refused easy answers, forcing readers to grapple with questions about evil, redemption, and the randomness of violence.

5. Stories from “The Martian Chronicles” by Ray Bradbury (1950)

Bradbury’s tales of Mars colonisation seemed like harmless science fiction until readers recognised the political commentary. Stories about book burning, thought control, and conformity pressure hit close to home during the McCarthy era, when political paranoia and accusations of disloyalty dominated American life.

“Usher II” depicts a future where imaginative literature is banned. The protagonist recreates Edgar Allan Poe’s House of Usher on Mars, then murders the censors who destroyed Earth’s libraries. Bradbury was clearly targeting contemporary censorship efforts.

School boards objected to anti-authority themes and criticism of censorship. Some banned the very stories that warned against banning books. The irony wasn’t lost on Bradbury, who saw his predictions coming true.

The stories remain controversial because they suggest that American society could slide into totalitarianism. Bradbury’s Mars becomes a refuge for free thinkers escaping Earth’s oppression. Cold War paranoia made these themes explosive.

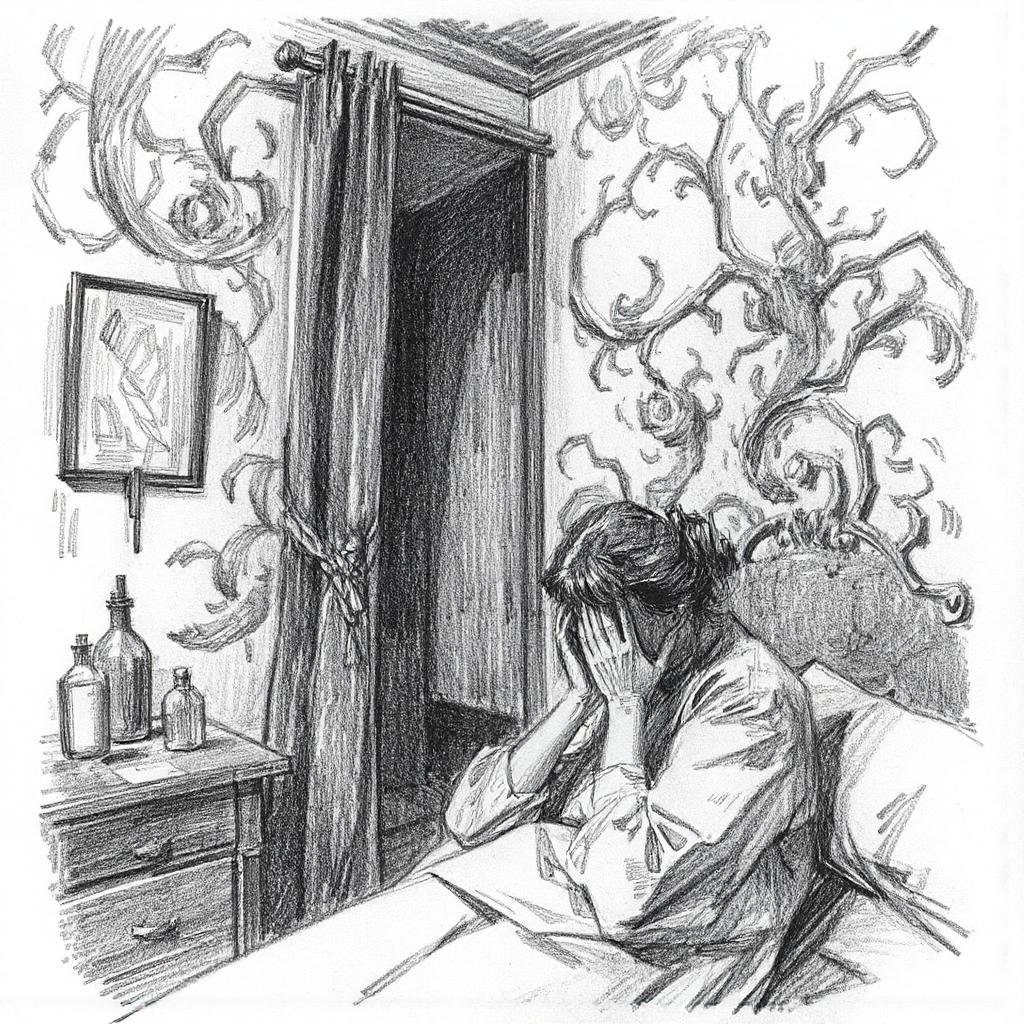

6. “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1892)

A woman’s slow descent into madness while confined for her “nervous condition” should have been recognised as brilliant psychological horror. Instead, it was suppressed for being “too depressing” and challenging medical authority.

Gilman’s narrator is imprisoned by well-meaning men who control her treatment. Her doctor husband dismisses her concerns, forbids intellectual activity, and isolates her from stimulation. The wallpaper in her room becomes her obsession as her sanity deteriorates.

The medical establishment was outraged. Gilman had based the story on her own experience with the “rest cure,” a treatment that confined women to bed and banned mental stimulation. Doctors felt personally attacked by her portrayal of their methods.

The story was largely ignored until feminist scholars rediscovered it in the 1970s. They saw it as a powerful indictment of medical gaslighting and women’s lack of agency. The debate continues as readers argue whether the narrator finds liberation or loses her mind completely.

These stories endure because they tackle subjects we’d rather avoid. They force uncomfortable questions about tradition, authority, marriage, violence, freedom, and sanity. Controversial fiction does more than shock; it makes us examine beliefs we haven’t questioned. That’s why these stories still have the power to disturb readers more than a century after they were written.

Leave a comment