The Mourning Portrait delves into the dangerous territory where grief meets desperation and love refuses to accept the finality of death.

In Victorian England, the emerging art of photography promised to capture truth with scientific precision. Yet some truths are too terrible for the rational mind to comprehend, and some forms of comfort exact a price far beyond what the bereaved imagine they’re willing to pay.

When sorrow makes us vulnerable, what manner of things might answer our call for reunion?

The Mourning Portrait

Dr Silas Ashford had been photographing the dead longer than the living, though he rarely spoke of it in polite company. In the autumn of 1889, when dry plate photography had finally liberated him from the burden of portable darkrooms, he found his services increasingly sought by those who wished to capture what remained when breath had departed. A final portrait of a beloved child, a family gathering around the deceased patriarch, a widow’s last moment with her husband before the earth claimed him—such commissions required delicacy, discretion, and an understanding that grief made people desperate for permanence.

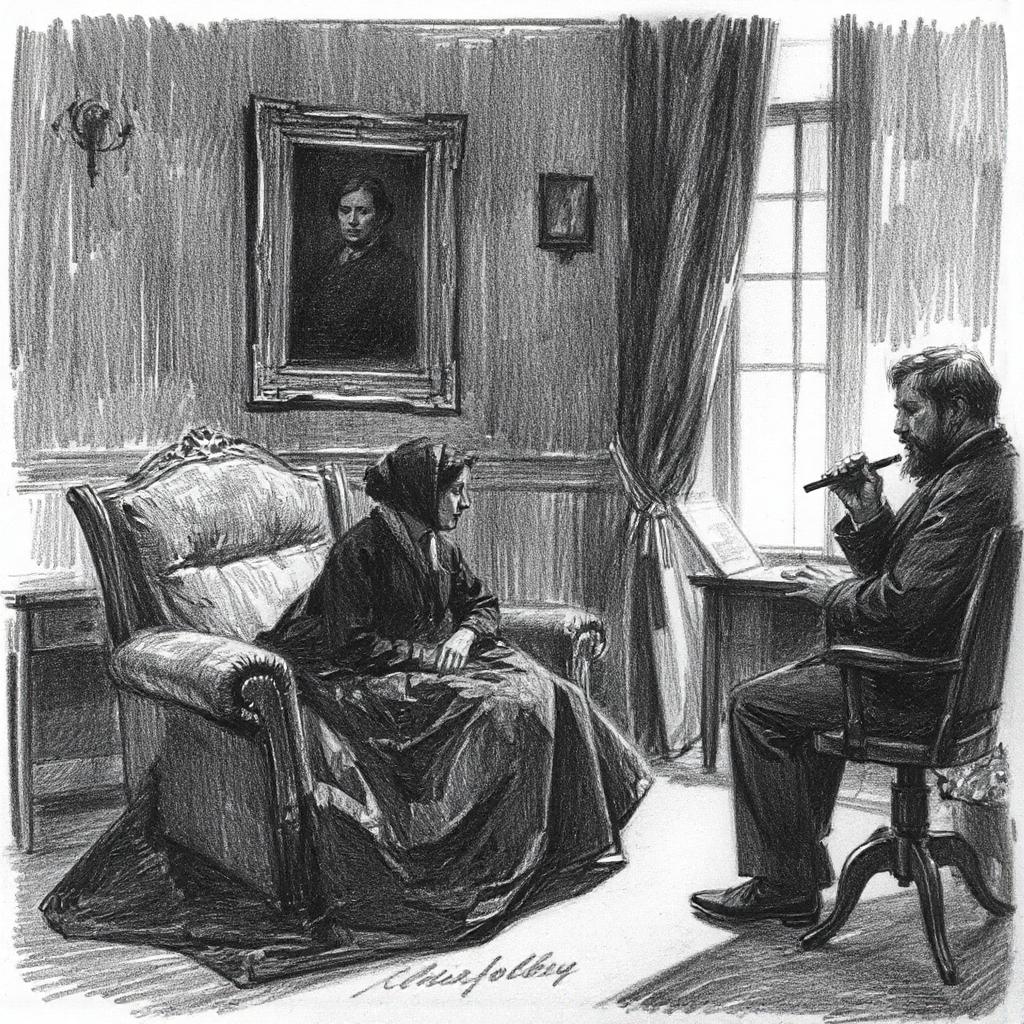

It was on a grey October morning that Mrs Clara Hartwell arrived at his Kensington studio, her mourning dress so fresh it seemed to absorb the wan light filtering through his north-facing windows. She moved with the careful precision of someone still learning to navigate the world without their anchor, each step considered, each gesture measured against the absence that now defined her days.

“Dr Ashford,” she said, her voice carrying the refined accent of someone educated beyond her station, “I require your assistance with a rather particular commission.”

Silas set down his lens cloth and regarded his visitor. She was perhaps thirty-five, with dark hair arranged in the severe style favoured by recent widows, though her face bore the kind of beauty that mourning could sharpen but not diminish. Her gloved hands clutched a small leather purse with white-knuckled intensity.

“I specialise in memorial photography, Mrs Hartwell. Please, do sit down.”

She perched on the edge of the velvet chair he indicated, her spine rigid. “My husband passed three weeks ago. Typhoid fever. Very sudden.” The words came out in the clipped manner of someone who had repeated them too often to officials, doctors, and well-meaning neighbours.

“I am very sorry for your loss.”

“Thank you.” She opened her purse and withdrew a small daguerreotype. “This was taken on our wedding day, seven years past. It is the only photograph I possess of him.”

Silas examined the image—a formal studio portrait showing a young couple, the man’s hand resting on his bride’s shoulder in the conventional pose. The husband appeared to be of middle years, with kind eyes and a carefully waxed moustache. Nothing unusual, except perhaps the slight blur around his figure, though that could easily be attributed to the limitations of earlier photographic methods.

“You wish me to make copies, perhaps? Or an enlargement for display?”

“No.” Mrs Hartwell’s grip tightened on her purse. “I wish you to photograph him as he is now.”

Silas looked up sharply. “I beg your pardon?”

“In our home. In his study. He spends most of his time there now, in his favourite chair by the window.” Her voice carried an odd note of satisfaction, as though she were discussing the habits of a living man.

A chill settled over the studio that had nothing to do with the October air. Silas had encountered grief in many forms—denial was among the most heartbreaking, but this seemed to venture into territory that made him profoundly uncomfortable.

“Mrs Hartwell,” he said gently, “I fear there may be some misunderstanding. Your husband has passed away. He cannot be—”

“I know what you think.” Her interruption was sharp, desperate. “But you are wrong. Death is not the ending we suppose it to be. Edmund has returned to me. He sits in his study each evening at six o’clock, reading his papers as he always did. I hear his footsteps on the stairs, the rustle of his newspaper, the clink of his brandy glass. He is there, Dr Ashford. He is simply… changed.”

Silas had heard such stories before—widows who heard their husbands’ voices in creaking floorboards, mothers who glimpsed their dead children in garden shadows. Grief played cruel tricks on the bereaved, conjuring presence from absence until the boundary between memory and reality dissolved entirely.

“I understand your pain, but perhaps it would be wiser to consult with your physician—”

“I am not mad.” The words came out like a whip crack. “I have tried to capture him with my own camera, but the images never develop properly. They remain blank, or show only empty rooms. But you are a professional. You understand light and shadow as I do not. Please.”

She reached into her purse again and withdrew a small roll of banknotes—more money than Silas typically charged for a week’s worth of commissions. He stared at the sum, thinking of his mounting debts, the rent due on his studio, the new equipment he needed but could not afford.

“I could not take payment for photographing empty rooms, Mrs Hartwell.”

“Then you accept that they may not be empty.”

There was something in her tone that made him look at her more carefully. Her eyes held not the wild gleam of madness, but the steady certainty of someone who had seen beyond the veil of ordinary experience. It was unsettling in its quiet conviction.

“One session,” he heard himself saying. “If I capture nothing of significance, you must agree to seek proper help for your grief.”

“And if you do capture something?”

Silas found he had no answer for that.

Mrs Hartwell’s house stood on a respectable street in Bloomsbury, its Georgian facade maintained with the kind of meticulous care that spoke of modest prosperity. She led him through rooms draped in black crepe, past furniture shrouded in dust sheets, to a study at the rear of the house that overlooked a small garden.

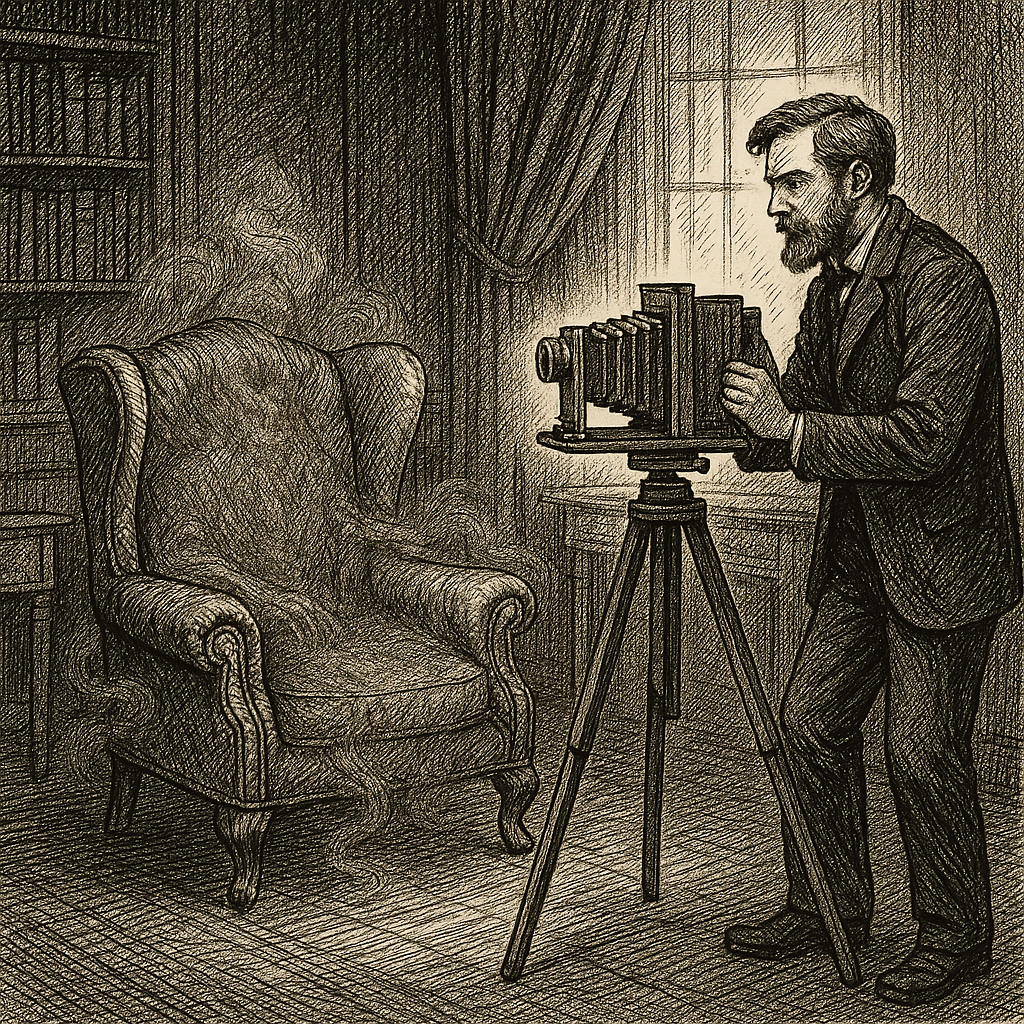

The room felt wrong the moment Silas crossed the threshold. Not obviously—the furnishings were conventional enough. A mahogany desk, leather-bound volumes lining the walls, a wingback chair positioned to catch the afternoon light from tall windows. But there was a heaviness to the air, a sense of occupation that had nothing to do with the living.

“He sits there,” Mrs Hartwell said, indicating the chair. “Always at six o’clock, when the light begins to fail.”

Silas consulted his pocket watch. Half past five. He began unpacking his equipment—the heavy wooden camera, the glass plates in their protective holders, the collapsible tripod. The familiar ritual of preparation usually calmed his nerves, but today his hands trembled slightly as he adjusted the focus.

“Tell me about your husband,” he said, hoping conversation might dispel the oppressive atmosphere.

“Edmund was a clerk at the Colonial Office. Very methodical, very precise. He believed in order, in reason, in the evidence of his senses.” A bitter smile crossed her face. “How ironic that he should return to prove all such certainties false.”

As she spoke, Silas became aware of subtle changes in the room. The light seemed to thicken, casting shadows that moved independently of their sources. The air grew colder, carrying the faintest scent of something he could not identify—not quite decay, but something adjacent to it, like flowers left too long in stagnant water.

“Mrs Hartwell,” he began, but she held up a hand for silence.

“Listen.”

At first he heard nothing beyond the usual sounds of a London evening—the clip-clop of horses, the distant cry of a street vendor. Then, gradually, he became aware of something else. Footsteps. Slow, measured, approaching from somewhere within the house.

“He comes up from the cellar,” Mrs Hartwell whispered. “I do not know what he does down there. I have not the courage to investigate.”

The footsteps drew closer, accompanied now by other sounds—the rustle of clothing, the soft scrape of something being dragged across the floor. Silas found his finger hovering over the camera’s shutter release, though he could not say why.

At precisely six o’clock, the wingback chair creaked.

Silas stared at the piece of furniture, his rational mind insisting that he saw nothing unusual. Yet something was occupying the chair—he could sense its presence as surely as he felt the floor beneath his feet. The leather cushions compressed under invisible weight, the wooden frame settling with the soft groans of well-used furniture.

“Do you see him?” Mrs Hartwell asked.

“I… there is something…”

Through his viewfinder, the scene appeared normal—an empty chair in a well-appointed study. But to his naked eye, shadows gathered around the furniture in patterns that defied the room’s lighting. The air shimmered slightly, like heat haze rising from summer pavements.

“Take the photograph.”

Silas pressed the shutter release. The flash powder ignited with its familiar whoosh and flare, flooding the room with brilliant white light. In that instant of illumination, he saw—or thought he saw—a figure in the chair. Not Edmund as he appeared in the wedding daguerreotype, but something else. Something that wore his shape like an ill-fitting garment, its edges blurred and indistinct, its face a suggestion of features rather than features themselves.

The light faded, leaving purple afterimages dancing across his vision. The chair appeared empty once more.

“Did you capture him?” Mrs Hartwell’s voice held barely contained excitement.

“I shall develop the plate and see. Such things cannot be determined immediately.”

But even as he spoke, Silas felt a growing certainty that he had captured something—and that whatever it was, it was not the beloved husband Mrs Hartwell believed she had been entertaining these past weeks.

That night, in the red-lit confines of his darkroom, Silas watched the image emerge from the chemical bath with growing unease. The plate developed normally at first, revealing the familiar outlines of the study—the desk, the bookcases, the windows overlooking the garden. But as the image gained definition, wrongness crept into the composition like ink seeping through paper.

The chair was occupied.

What sat there bore only passing resemblance to the man in the wedding photograph. It was as though someone had attempted to recreate Edmund Hartwell from imperfect memory, getting the broad details correct but failing utterly with the specifics. The face was too long, the limbs too angular, the proportions subtly but disturbingly wrong. Worse still, the figure seemed to be aware of the camera, its malformed features turned toward the lens with an expression of such malevolent intelligence that Silas stumbled backward, knocking over his chemical tray.

As the developer spread across the floor, eating into the wooden boards with its caustic hunger, he stared at the photograph in the fixing bath. In the harsh red light of the darkroom, the thing in the chair appeared to move, its head tilting at an impossible angle, its mouth—if mouth it could be called—stretching into something that might charitably be called a smile.

Silas snatched the plate from the chemicals and held it up to the safety light. The figure remained motionless now, frozen in its awful parody of domestic contentment. But around the edges of its form, he could make out other shapes—indistinct figures crowding behind the chair, their features even more degraded than their apparent master’s. How many were there? Dozens? Hundreds? The shadows seemed to writhe with half-formed bodies, as though the house had become a gathering place for things that could not quite manage to be human.

He thought of Mrs Hartwell, alone with her delusion, serving tea to something that wore her husband’s name but had never known his love. How long had it been feeding on her grief? How long before it tired of the masquerade and revealed its true nature?

The photograph seemed to pulse in his hands, the figures behind the chair pressing forward as though trying to escape the confines of the image. Silas forced himself to look more closely at the thing in the chair. Its clothing was wrong—not the conventional dress of a Victorian gentleman, but garments that seemed to shift and flow like smoke. And its hands… its hands were not hands at all, but something more akin to roots or tendrils, growing from its sleeves and spreading across the chair’s armrests like fungal growths.

He had to warn Mrs Hartwell. Whatever had taken residence in her home, it was not her husband, and it was not benign. But even as he reached for his coat, Silas found himself wondering: would she believe him? Or would grief and longing blind her to the evidence of her own eyes?

The photograph lay on his workbench, the chemicals still drying on its surface. In the red light of the darkroom, the thing in the chair seemed to be watching him, waiting to see what he would do with the terrible truth he had captured.

Silas wrapped the plate in brown paper and placed it in his coat pocket. Whatever Mrs Hartwell chose to believe, she deserved to know what manner of guest she had been entertaining. He only hoped he would not be too late to save her from the thing that had made its home in her grief.

As he left the darkroom, he could have sworn he heard the sound of footsteps following him into the darkness—slow, measured, and accompanied by the soft rustle of clothing that moved like shadows made manifest.

Leave a comment