Classic Shorts

As well as entertaining us, great short stories actually teach us how fiction really works. In Classic Shorts we take a closer look at the stories that have stuck around, not because they’re assigned reading, but because of the emotional impact they had on readers when they first appeared. We’ll explore what makes these tales tick, why they still pack a punch decades later and what modern writers can learn from them.

Classic Shorts aren’t intended to be academic essays. Think of them as conversations about craft, the kind you might have with a fellow reader who’s just discovered something brilliant and wants to share it.

Lost Hearts

When M.R. James published Lost Hearts in 1904, he was still a relatively unknown writer of ghost stories. Yet this early tale contains every element that would make him the master of supernatural horror: the scholarly antiquarian hiding monstrous secrets, the isolated country house, and children who return from the dead seeking terrible justice. What’s most remarkable is how fully formed James’ distinctive style already was. While other writers spent years finding their voice, James emerged with his technique perfectly intact.

Lost Hearts remains one of his most disturbing stories because it takes something we consider noble (the pursuit of knowledge) and reveals the horror that can lurk beneath academic respectability.

Stop Right Here

If you haven’t read Lost Hearts, go and read it now. It’s about 4000 words, roughly twenty minutes of your time. This analysis discusses the story’s shocking conclusion and the fate of young Stephen Elliott… so spoilers follow.

The Monster in the Library

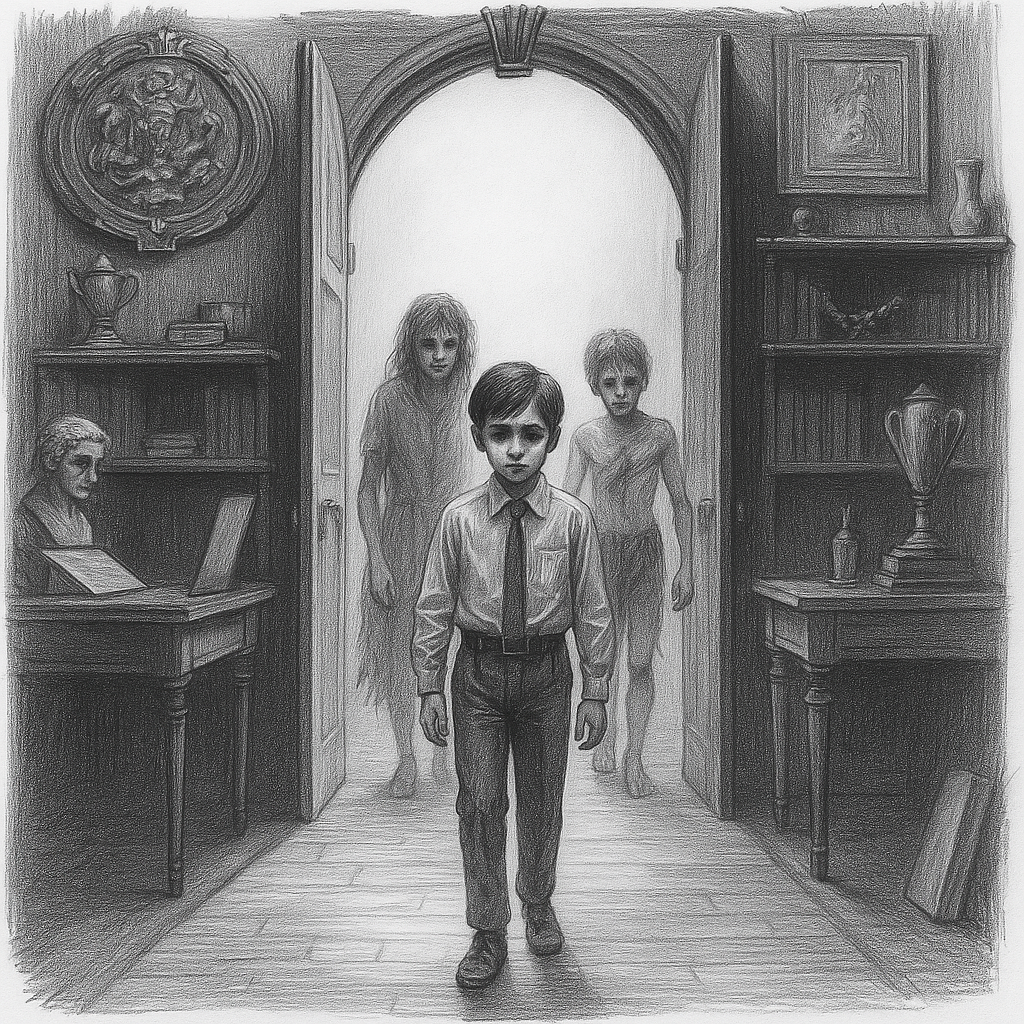

James opens with twelve-year-old Stephen Elliott arriving at his elderly cousin’s estate, Aswarby Hall. Mr Abney seems the perfect Victorian gentleman scholar: learned, cultured, devoted to his books on ancient religions. The house is filled with classical sculptures and scholarly volumes. Everything suggests civilisation and safety.

But James plants his clues immediately. Mr Abney asks Stephen’s age twice within minutes, then carefully notes it down “in his book.” He’s particularly interested in Stephen’s birthday: “Eleventh of September, eh? That’s well—that’s very well. Nearly a year hence, isn’t it?”

A year hence. James doesn’t explain why this matters, but the phrase hangs in the air like a threat.

The genius of James’ approach is how he uses Stephen’s innocent perspective to amplify our dread. The boy sees only kindness in his cousin’s behaviour, but we sense something predatory in that intense interest in his age and birthday. James understood that horror works best when the victim doesn’t recognise the danger.

The Ghosts of Previous Victims

Through Mrs Bunch, the housekeeper, we learn about Mr Abney’s previous “charity cases”: a gypsy girl and a foreign boy with a hurdy-gurdy, both of whom mysteriously disappeared. James presents these disappearances as ordinary misfortunes: restless children running away. Yet we begin to suspect something more sinister.

When Stephen dreams of a figure in the old bathroom, James gives us one of his most haunting images: “A figure inexpressibly thin and pathetic, of a dusty leaden colour, enveloped in a shroud-like garment, the thin lips crooked into a faint and dreadful smile, the hands pressed tightly over the region of the heart.”

This ghost is actually a victim trying to warn Stephen. The hands pressed over the heart become crucial later, when we discover how Mr Abney’s victims died. James uses the supernatural to reveal the truth about the past while foreshadowing Stephen’s intended fate.

Academia as Horror

What makes “Lost Hearts” particularly unsettling is how James corrupts the figure of the scholar. Mr Abney appears as a respected antiquarian, a contributor to learned journals. His evil emerges from legitimate academic pursuits twisted to monstrous ends.

The story’s climax reveals Mr Abney’s true project: following ancient texts, he believes that consuming the hearts of three children will grant him supernatural powers. He’s already murdered two victims; Stephen is meant to be the third. The horror lies in the methodical, scholarly approach to child murder.

James shows us Mr Abney’s notes, written in the dispassionate style of academic research: “The best means of effecting the required absorption is to remove the heart from the living subject, to reduce it to ashes, and to mingle them with about a pint of some red wine, preferably port.”

The clinical language makes the horror worse. This represents carefully planned evil disguised as intellectual inquiry, without passion or madness.

Justice from Beyond

The story’s conclusion is both satisfying and terrible. Stephen arrives at Mr Abney’s study to find his cousin torn apart by his own victims. The dead children have returned to exact their revenge. The boy with the gaping wound in his chest has finally found his killer.

James’ description of Mr Abney’s corpse mirrors the wounds he inflicted: “In his left side was a terrible lacerated wound, exposing the heart.” The punishment fits the crime perfectly. The hearts he stole have been reclaimed with interest.

Yet this represents cosmic horror rather than simple justice. The supernatural children become creatures of terrible purpose, waiting three years for their revenge, growing stronger as the anniversary of Stephen’s planned murder approaches.

The Template for Modern Horror

“Lost Hearts” established the template that countless horror writers would follow. The idea that knowledge itself could be dangerous, that scholars and intellectuals might harbour the darkest secrets, became a staple of the genre. James showed that horror could emerge from libraries as easily as graveyards.

The story also demonstrates James’ understanding of childhood vulnerability. Stephen’s innocence makes him the perfect victim. He trusts his educated cousin completely. The horror emerges from the betrayal of that trust, the corruption of protective relationships.

Why It Still Works

“Lost Hearts” remains disturbing because it taps into primal fears about the people we trust. Teachers, doctors, scholars: figures of authority who might abuse their power. In our age of institutional scandals and academic controversies, Mr Abney’s scholarly evil feels depressingly contemporary.

James also understood that the most effective horror comes from the corruption of civilised values. Mr Abney represents everything we associate with culture and learning, yet he’s planning ritualistic child murder. The disconnect between his genteel manner and monstrous intentions creates lasting unease.

The story works because it suggests that beneath our civilised surface lurk ancient, terrible hungers. Knowledge can make us more dangerous rather than better.

For a writer’s second published ghost story, “Lost Hearts” shows remarkable confidence and skill. James had already mastered the art of making the familiar sinister, of finding horror in the most respectable places. He would refine his technique over the years, but the essential elements were already perfectly in place.

Sometimes the most frightening monsters are the ones who’ve read all the books.

Leave a comment