Step into The Gothic Hour, where shadows grow longer and the past refuses to stay buried! These stories draw from the rich tradition of classic horror. Think creaking floorboards, ancient curses, and secrets that span generations, while keeping one foot firmly planted in the modern world. Here you’ll find cursed heirlooms in contemporary homes, museum artefacts with malevolent intentions, and family legacies that refuse to die. Here, we’re not interested in cheap thrills or gore. Instead, The Gothic Hour offers the slow-burning dread that made writers like Poe and M.R. James masters of their craft. These are stories that understand the most terrifying horrors often wear the mask of respectability, hiding in plain sight until the moment they reveal their true nature.

Museum Piece

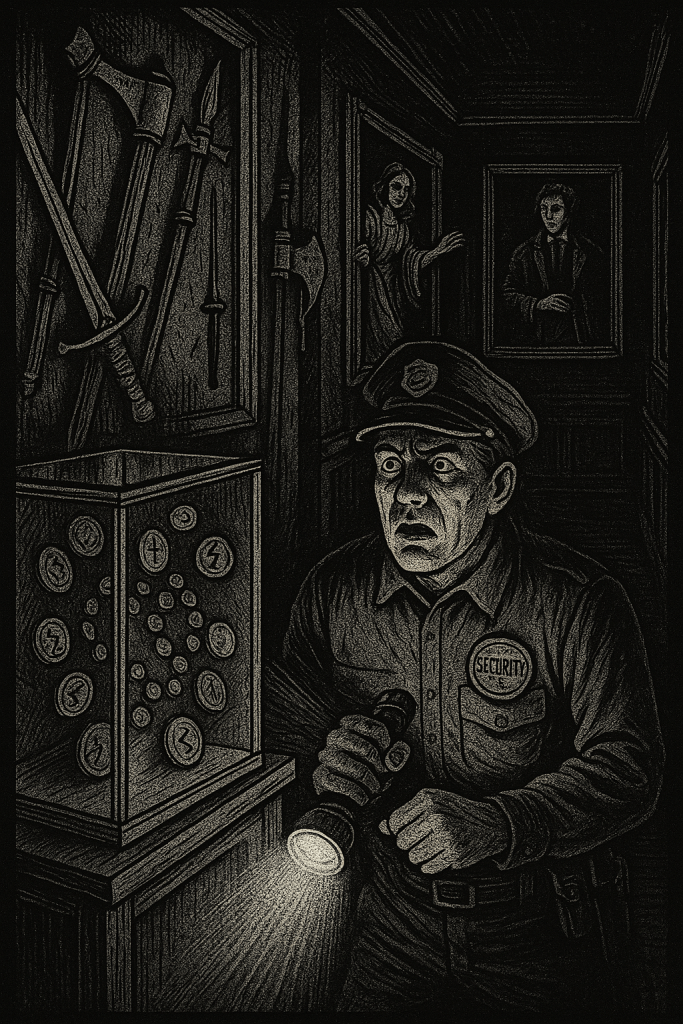

Thomas Fletcher had spent seven years walking the corridors of the Whitmore Museum after closing time, and in all that time, he had developed the peculiar habit of speaking to the artefacts as though they were old friends. Not from loneliness, he would have insisted if asked, though no one ever did ask. Rather, it was the weight of their silence that compelled him to fill the darkness with his voice—these fragments of civilisations that had once meant everything to someone, now reduced to placards and climate-controlled cases.

The museum at night possessed a character entirely different from its daytime self. Gone were the chattering school groups and tourists with their cameras. In their place settled a profound quiet that seemed to emanate from the very walls, as though the building itself held its breath. Thomas had grown fond of this transformation. Where others might find the shadows oppressive, he found them companionable. The Roman gallery, with its marble emperors gazing eternally into middle distance. The Mediaeval hall, where suits of armour stood sentinel over cases of illuminated manuscripts. The Egyptian wing, where sarcophagi waited with infinite patience.

It was in the Roman gallery that Thomas first noticed the coins.

They sat in their case as they always had—a collection of aureus and denarius pieces spanning three centuries of empire. Thomas knew them well; he had paused before this particular display countless times, reading aloud the Latin inscriptions to practise the pronunciation he’d learnt from library books. But on this Tuesday evening in November, something was different.

The coins had been arranged in neat rows when he’d made his first round at ten o’clock. Chronological order, earliest to latest, left to right. Standard museum practice. Now, at half past midnight, they formed a rough circle.

Thomas frowned, pulling his torch from his belt to examine the case more closely. The glass showed no signs of tampering. The lock remained secure. Perhaps the afternoon curator had rearranged them for some reason—though why anyone would abandon the chronological display escaped him.

He made a note in his log and continued his rounds.

The next night, the coins had formed letters. Not English letters, but something that looked almost like Latin script. Thomas squinted at them through the glass, trying to make sense of the arrangement. The shapes were crude, imperfect, but they resembled words he’d seen in his Roman history books.

“Very funny,” he said aloud to the empty gallery. “Which of the day staff has been having a laugh?”

But even as he spoke, doubt crept into his voice. The museum employed three curators, all of whom treated their artefacts with reverence bordering on obsession. None would risk damage to the collection for the sake of a practical joke.

Thomas photographed the arrangement with his mobile phone, then settled into the security office to research. By morning, he had translated the rough letters: CAVE—beware.

He said nothing to the day supervisor about the coins. Instead, he began to watch.

Over the following week, the pattern escalated. The coins rearranged themselves nightly, always forming new Latin words or phrases. FUGE—flee. MORS VENIT—death comes. NOLI MANERE—do not remain. Each morning, they returned to their proper chronological order, as though the day shift’s very presence restored normality.

Thomas told himself there had to be a rational explanation. Vibrations from passing traffic. Settling of the building’s foundations. Microscopic shifts in temperature affecting the display case. But his explanations grew thinner each night as the messages grew more urgent.

The breakthrough came on a Thursday, when Thomas arrived to find that the coins had arranged themselves into a date: ANTE DIEM KALENDAS—before the first day. It took him most of the night to work out the Roman calendar conversion, but when he did, his blood chilled. The coins were warning him about the winter solstice. Three weeks away.

That same night, the Viking axe began to show bloodstains.

The weapon hung in the Mediaeval hall, a brutal thing of iron and wood that had once split skulls on English battlefields. Thomas had always given it a wide berth—something about its presence had never sat well with him—but tonight he found himself drawn to examine it more closely.

Fresh blood clung to the blade’s edge. Not rust, not oxidisation, but actual blood that gleamed wetly in his torchlight. As he watched, transfixed, a single drop fell from the metal to the floor below.

Thomas reached for his radio to call this in, then stopped. What would he say? That a thousand-year-old axe was bleeding? They’d have him committed or sacked, possibly both.

Instead, he began to document everything. Photographs, measurements, detailed notes about each anomaly. The Egyptian canopic jars that whispered in ancient tongues when he passed. The Renaissance mirror that reflected faces from centuries past instead of his own. The Anglo-Saxon burial goods that rearranged themselves into funeral patterns.

By the second week, Thomas understood that the museum had moved beyond simply housing the past—it was becoming permeable to it. Each artefact served as an anchor point, a connection between then and now that grew stronger with each passing night.

The paintings were the worst. Thomas had always avoided the portrait gallery during his rounds, finding something unnerving about those painted eyes that seemed to follow his movement. But now he could no longer ignore them. The subjects moved within their frames. Subtly at first—a slight turn of the head, a shifting of hands—but with increasing boldness as the solstice approached.

Lady Margaret Ashworth, painted in 1587, would smile at him as he passed. Her teeth were black with Tudor decay. Sir Edmund Blackwood, captured in oils during the Restoration, would whisper courtly greetings that carried the scent of plague and perfume. The anonymous gentleman from the Georgian era would bow formally, his powdered wig shifting clouds of dust that Thomas could smell despite the sealed frame.

They were trying to speak to him, Thomas realised. All of them. The entire collection was attempting to communicate across the centuries, and the winter solstice was somehow the key to their efforts.

On the night before the solstice, Thomas arrived for his shift to find that every artefact in the museum had changed position. The Roman coins spelled out a single word: VENIMUS—we come. The Viking axe had fallen from its mounting, embedding itself in the wooden floor. The Egyptian sarcophagi stood open, their mummy wrappings trailing across the tiles like discarded skin.

And in the portrait gallery, every painted figure had turned to face the same direction. Towards the centre of the room, where a new portrait hung—one that hadn’t been there the night before.

It showed Thomas himself, dressed in the blue uniform of museum security, standing amid the darkened galleries. But his face held an expression of terror he’d never worn, and his eyes stared out with the flat, lifeless gaze of all the museum’s other subjects.

Beneath the painting, a small brass plaque bore an inscription: Thomas Fletcher, 1985-2023. Night Security Guard, Whitmore Museum. The final addition to our collection.

Thomas stepped back from the portrait, his heart hammering against his ribs. The other painted figures watched him with anticipation, their centuries-old faces animated with a hunger he finally understood.

They weren’t trying to communicate with him. They were trying to join him. And tomorrow night, when the solstice granted them their full power, they would succeed.

Thomas Fletcher turned and ran from the gallery, his footsteps echoing through corridors that no longer felt familiar. Behind him, he could hear the whisper of canvas and the creak of ancient wood as every portrait began to step from its frame.

But the museum doors, when he reached them, would not open. The locks had changed to match those of centuries past—great iron mechanisms that required keys long since lost to time.

Thomas had already become part of the collection. He simply hadn’t realised it yet.

He pulled out his mobile phone to call for help, but the screen showed only the date: December 21st, 1347. The Black Death year. Around him, the museum began to change, the electric lights flickering and failing as torches sparked to life in wall sconces that hadn’t existed moments before.

Through the windows, Thomas glimpsed not the familiar streets of the modern city, but thatched cottages and muddy lanes where plague victims lay unburied.

The past had abandoned any attempt to communicate with the present. Now it meant to claim it.

Thomas Fletcher smiled with lips that no longer belonged to him, and took his place among the museum’s eternal collection.

Leave a comment